Digitally native retailers, including DTC brands, sell goods in just about every category, from exercise bikes to lingerie, razors to luggage. But through the years, as they’ve pitched venture capitalists, wooed shoppers, stolen market share and disrupted retail, their basic business models have had much in common.

They operate online, without stores or retail partners. Thanks to that, they easily vacuum up shopper data and keep customer relationships all to themselves. With no rent to pay or physical locations to run, their margins, theoretically, are fatter. And without wholesale, their customers pay full price, directly to them.

But of course, the devil’s in the details. Many digital natives have strayed from their original visions, often in the very ways that purported to make them disruptive in the first place, in an attempt to achieve scale and/or profitability.

“Probably the first domino to fall was ‘you don't have to run stores,’” Rick Watson, founder and CEO of RMW Commerce Consulting, said by phone. “Then the second thing that happens is, a lot of these DTC brands, like Harry’s, have been acquired by bigger consumer product companies. And now folks like Allbirds and others are prioritizing wholesale. Wholesale is cool again.”

Several DTC brands and marketplaces, including Glossier, The RealReal, Casper, Warby Parker, ThirdLove, Peloton, Allbirds, Away, Lively and Wayfair, have opened brick-and-mortar stores. Increasingly, more are also turning to wholesale, which turns out to be an effective channel for boosting sales and margins.

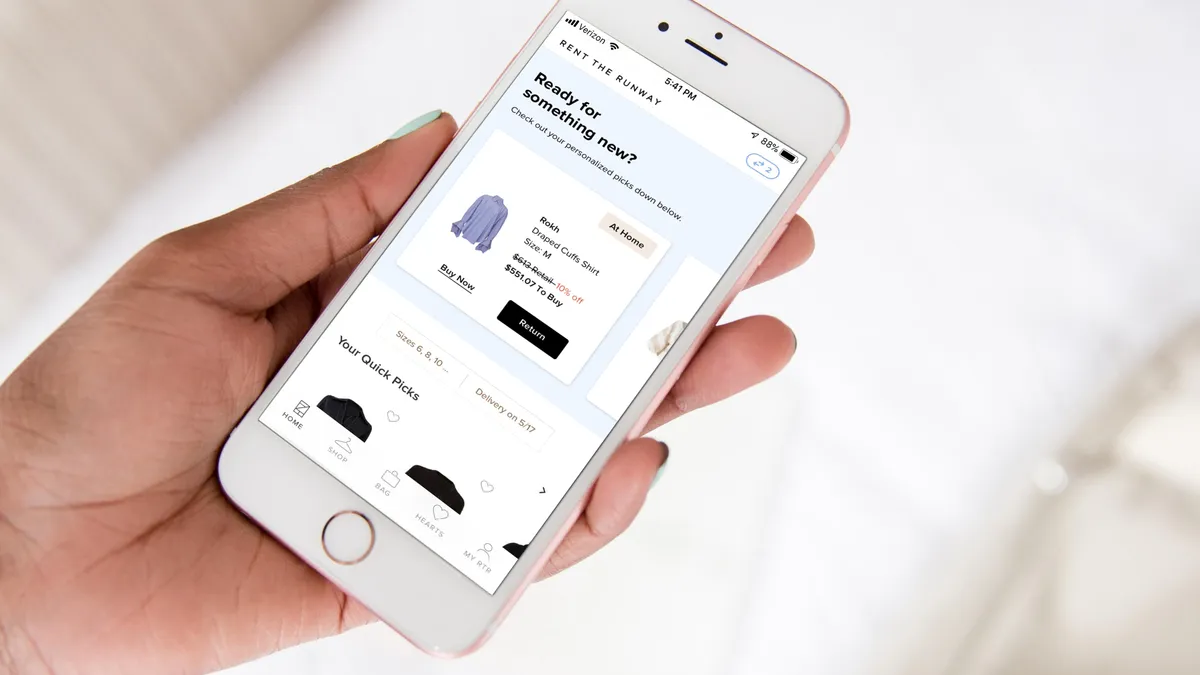

Some continue to change up other aspects of their sales approach. In recent years, for example, Rent the Runway has: introduced various new subscription tiers; dropped unlimited rental; added kids and (with a retail partner) home decor; offered sales of previously rented clothing; opened those sales to non-subscribers; partnered with a retailer to sell those garments; partnered with retailers and hotels for pickup and dropoff; opened then closed its own physical locations; and developed exclusive designs.

Stitch Fix has similarly shifted its approach numerous times. The box e-retailer expanded to the U.K., added men’s and kids’ clothes to its offer, allowed box subscribers to buy garments a la carte, provided previews of curated boxes so customers could reject or accept certain items, opened its a la carte website to all consumers, added a search function to that site, then restricted it once again to only those who have ordered a box.

Exercise bike company Peloton has scrambled to adjust prices and make other changes after its pandemic-era boom fizzled. Those that are dependent on clients signing up for a membership are grappling with the decline of that model, according to Watson. ThredUp and Nordstrom appear to have taken that note, as both shut down their curated box services in the last couple of years.

“I think people are subscriptioned out,” Watson said. “So I think they're grasping at straws a little bit. They need to find a next act. That's definitely Stitch Fix. RealReal just has pretty major profitability issues. If they sold higher-margin goods, maybe they can charge more and turn a profit on those things. The challenge is, the site then becomes so exclusive that how many items are those in the world?”

Expanding what turns out to be, for many digital natives, a niche customer base is getting harder as venture capital money has dried up and customer acquisition costs have soared, Watson also said. Fundamentally, more of these companies, including of late Thirteen Lune, Our Place and Vuori, realize the tweak they need most is selling through brick and mortar.

"Regardless of the model that a DTC adopts, the math simply doesn’t support an online pure-play retail model of any kind that can be sustained against those that have a physical presence and can copy whatever someone else does online,” Forrester Principal Analyst Brendan Witcher said by email. "Not enough consumers have shown the propensity to remain long-term, loyal customers of a pure-play, online-only retailer. If they did, these companies would not have to spend the millions of dollars in advertising and marketing that wipe out their profitability.”

While the pandemic super-charged e-commerce, that acceleration will serve to slow its growth somewhat over the next year or two, especially as consumers return to stores, according to Euromonitor Senior Consultant Rabia Yasmeen. The first wave of e-commerce’s disruption is giving way to a new era, she said by email.

“As current trends clear the path ahead for physical retail – we can see the next development of retail would see integration of physical and digital, with one supporting the other,” she said. “Hence, years of dynamic, double digit e-commerce growth are likely to be only seen in the case of unusual circumstances.”