Doug Stephens' expertise is grounded in the past: Behind him are two decades of executive experience and two books, "The Retail Revival: Re-Imagining Business for the New Age of Consumerism" and "Reengineering Retail: The Future of Selling in a Post-Digital World."

He calls himself (and his consulting business) "the Retail Prophet," however, in light of his focus on the future.

As we round the corner of the 21st century's second decade, a time of reckoning for retail, we asked for his view of the industry as the next 10 years unfold.

The following discussion was conducted between Stephens and Retail Dive Senior Reporter Daphne Howland over email, and has been edited for length and clarity.

RETAIL DIVE: For the past decade, legacy retailers for the most part seem to have finally embraced online and even all-channel commerce. In the next decade, how much more evolution do you foresee? What, if anything, is holding e-commerce back?

DOUG STEPHENS: Where we find ourselves today is at the end of the beginning of e-commerce. In 2019 a little more than $3 trillion dollars in global retail was transacted online and was largely comprised of the sorts of products that are relatively simple to transact — electronics, airline and event tickets, shoes, and a range of other commodity items. However, the outstanding opportunity is $27 trillion remaining in the global retail economy, including things that are fundamentally more complex purchases.

What items that we think of as resistant to e-commerce do you see shoppers increasingly buying online?

STEPHENS: I project that by as early as 2033 the majority of our daily consumption will be transacted online. We also sit on the cusp today of what I call the Replenishment Economy.

But things such as automobiles, jewelry, real estate, perishable food items, pharmaceuticals, home furnishings, luxury items and home improvement products — these and other complex product categories represent the next frontier of online commerce, and companies like Alibaba, Amazon, JD.com and others will be aggressively working to unlock revenue in each.

To do this they'll be exploring a range of new platforms, systems, shipping capabilities and technologies to dramatically improve consumer confidence in buying these categories online. The whole concept of how we shop online will also change dramatically.

The future of retail will see complete integration of technologies like augmented and virtual reality, the internet of things, sensor-driven packaging and connected appliances. This will result in an exponential impact on e-commerce volumes.

Meanwhile, though, doesn't brick and mortar remain fundamental to retail, even if it often also seems behind?

STEPHENS: In the future, all but the most convenience-based retailers will begin to use their stores as media to acquire customers and their media platforms as stores to transact sales.

Put another way, media is now a cost of sales and rent is now a cost of customer acquisition. Retailers that miss or ignore this shift will do so at their peril.

What mistakes are retailers making with their stores, and how do you see physical stores evolving?

STEPHENS: Here's what we sometimes forget. If you stand on any metropolitan street corner in North America, 99% of the retail you will see around you was built to succeed in the 20th century. Sadly, this means it's built to fail in the 21st century. To understand why, one has to appreciate that the old model for retail relied almost exclusively on paid media and advertising to drive consumers down the purchase funnel to physical stores to purchase goods.

This is no longer the case. Increasingly, media, in all forms, is becoming the "store." The fact is that 66% of the time, when it occurs to an American consumer that they need a product, they're going directly to Amazon to search for it. Not a mall, shopping center or store, but Amazon. In essence, media (in a variety of forms) is becoming the store. Online merchants can display more products, provide more accurate and robust product information, and transact seamlessly in one click. Media is not merely becoming the store, it's becoming the ultimate store.

Conversely, however, physical stores are going through a very different but corresponding evolution. Brick-and-mortar stores are no longer simply a channel for the distribution of products. They no longer act as the final point in the purchase funnel.

So stores won't disappear, but how important will they be?

STEPHENS: Physical stores are becoming a powerful media channel, and very often the first point of contact between brands and consumers. As consumers become increasingly technologically entrenched, they'll crave far more and better physical retail experiences. And so brick-and-mortar spaces will offer retailers and brands the opportunity to draw the consumer into the brand story, deliver a remarkable and immersive brand and product experience, and ultimately galvanize their relationship with consumers. A relationship that can then live across multiple buying channels.

Physical stores will not only be a powerful media channel, but also the most manageable and measurable media channel in financial terms.

In the next decade, what are the forces retailers must contend with in order to succeed?

STEPHENS: There are a wide variety of challenges facing retailers. The polarization of wealth and incomes will continue to gut the middle class in most developed economies. Baby boomers will continue to spend less, thus requiring brands to figure out the needs and sensibilities of younger consumers. Technology continues to advance at unparalleled speed. Globalization is shrinking the world and bringing a never-ending procession of challenger-brands to the market.

But all of these challenges are surmountable, provided a company has the right leadership. Hence, the most important challenge and opportunity into the future is establishing effective leadership itself.

What does "effective leadership" entail?

STEPHENS: The leader of the future must do several things.

They must condition boards and investors to accept an atmosphere of constant experimentation, iteration and change. They must instill curiosity in their teams and a willingness to think laterally and divergently about possibilities, as opposed to the linear and convergent thinking most employ today. The leader of the future has to constantly be pushing the organization out of its safe space and challenging the status quo. They must be willing to step just beyond their current understanding and do unprecedented things, often with little to no supporting data. They must be calculated risk-takers with a knack for building talented teams.

And finally, they need to constantly be trying to develop concepts that put their current concept out of business. That sounds counterintuitive to a lot of leaders, but it's vital. You have a choice to either create the thing that kills your current business or wait for someone else to do it. It's a lot better to own the disruption.

You mention the decline of the middle class. What has that meant for the last decade, and what does it mean for the next?

STEPHENS: Our entire Western, post-WWII frame of reference in retail is built on the concept of a robust, enduring and growing middle class that aspired to the mid-tier trappings of success. Most pricing systems were bell-curved on the basis of "good, better, best," knowing that most consumers would choose "better." And until the early 1980's that was the case.

Over the last 40 years, however, we've seen the middle class steadily gutted, by virtue of polarized education levels, incomes and wealth. We've seen labor unions weakened and blue collar work relegated offshore or, more often, to technology. The result is that our middle class democracies have become societies of haves and have-nots.

The problem is that many retailers like Sears, J.C. Penney, Kohl's and others who traditionally catered to the middle class continue to do so, despite the fact that their customers are disappearing. Retailers have to choose which of these societal segments they're serving. There is no "good, better, best" anymore. You're either "good enough" or you are the best. The bottom line is, if you're a mid-tier retailer selling mediocre products at average prices with an okay customer experience, you may as well close up shop now.

Some see this decline as a failure of policy or government responsibility. Do you think retailers have any obligation to get politically involved to revive the middle class?

STEPHENS: I think the onus is more on consumers to get involved. After all, it's been the consumer's lust for cheap products that has given rise to Walmart and other big box deep discounters, pushed retailers to stagnate retail wages and inspired the fast-fashion movement, as well as online predators like Amazon. As much as I'd like to believe that retailers will altruistically save the middle class, consumer action and political involvement will ultimately be the catalyst.

In light of that reality, do you think consumers are becoming less materialistic or is it more that they can't afford as much?

STEPHENS: There's no question that consumers are moving more of their spending to experiences over products. According to one study, more than three quarters of millennials surveyed indicated they'd prefer to spend money on experiences with friends and family as opposed to products. We've seen sharp increases in spending on categories like entertainment, live concerts, restaurant and travel. Hence, plays by retailers like LVMH, which is getting deeper into the hospitality sector through its Belmond acquisition.

What's driving that desire for experience? And what are the implications for retailers, which, after all, sell things?

STEPHENS: Part of what's driving that trend is social media. Experiences have become the social currency of a new generation of consumers who have commemorated every meaningful life experience online. Experiences, not products, play best on social. I'd argue that increasingly, experiences really are the product itself. The actual product is almost a souvenir.

There is also the new financial reality. While millennial incomes have finally come up to speed with previous generations, their wealth and net assets continue to trail. Many continue to shoulder significant student debt and the cost of home ownership is out of reach for many.

This has created a triple-whammy for retailers. Today they have to serve infinitely more discerning and informed consumers, pressed by lower net wealth and higher debt, who also have a bias toward experiential spending. For any retailer calibrated to serving baby boomers for the last 30 years, it means a complete overhaul of the business and a rethinking of their customer experience.

With such complexities, what will it take for a retailer to understand its customer?

STEPHENS: When most retail businesses are founded, the owner usually has an intimate knowledge of their customers because they spend much of their time interacting with them. In some cases, the owner themselves is a consumer of the product and so innately understands the needs and preferences of their customers from personal experience. As organizations scale, this intuitive understanding dissipates, and leadership loses touch with the needs of the customer.

That's when power and decision-making move away from the front lines of the business toward the middle of the organization. And instead of speaking to customers directly, companies hire research firms and conduct studies and focus groups — none of which can replace the intimacy and immediacy that the company has lost with its customer base. Instead of emanating from the front-line, strategy begins to roll downhill, often disconnected from the customer reality. And eventually the dissonance between the company, its employees and its customers becomes fatal.

So the challenge for organizations is to push power, autonomy and decision-making back to the front lines and to let information from the front lines inform the broader strategy. In order to accomplish this, the structure of the company and its compensation programs have to promote such a dynamic.

So is "knowing your customer" a universal, age-old phenomenon? Or is this, too, evolving? Put another way — what remains the same about, say, a mid-20th century department store customer and the customer of today and of the future?

STEPHENS: In general, we need to focus a lot less on the nuanced differences in needs between individual consumer segments or demographic cohorts. We've become obsessed with segmenting consumers into "personas" or "archetypes," each with sometimes diametrically different needs.

Brands and retailers would be wiser to build their value proposition to address deeper, more universal human needs. The need for security, recognition, belonging, entertainment, inspiration, purpose and respect etc. — these are things every human wants and needs. If more retailers focused on mastering these broad human needs, as opposed to buying into demographic and psychographic profiling, we'd have a much lower failure rate in retail.

Technology has both challenged and enabled retailers in the past decade. What technology on the horizon do you believe will be important for the retail industry to understand or embrace?

STEPHENS: First, my response as a business advisor is, it depends! The most important technology on the horizon depends subjectively on a company's market positioning, brand essence and customer experience. I always recommend that a brand work backward from their customer experience design to choices about technology.

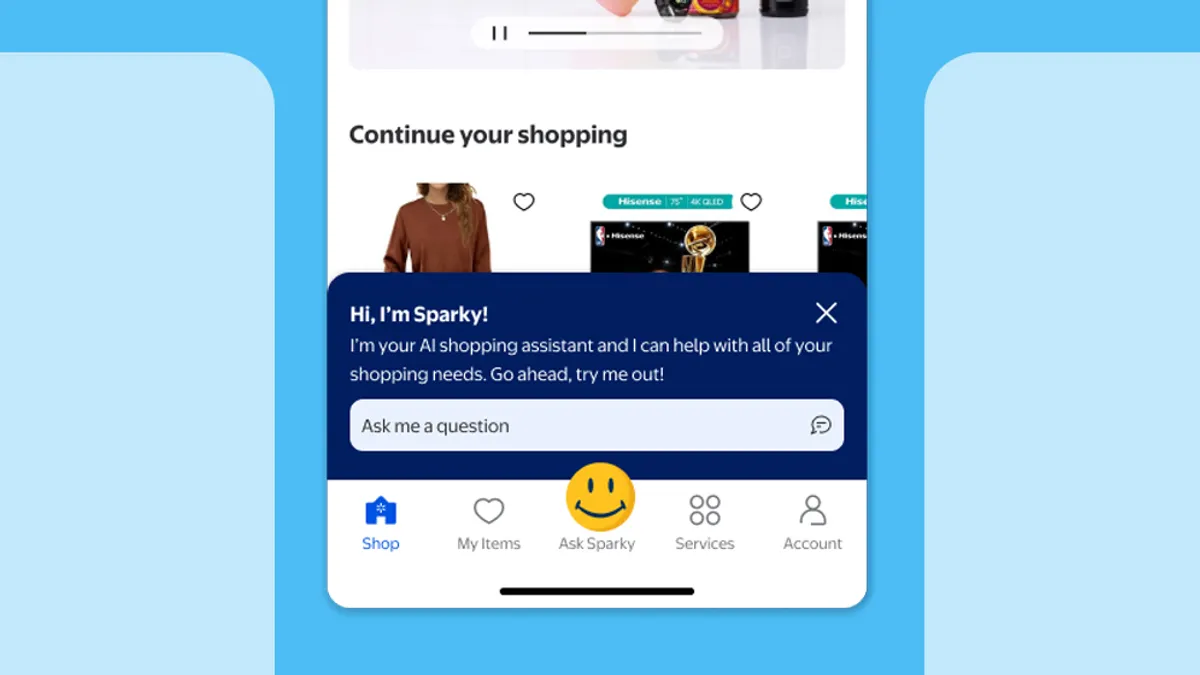

For example, for Walmart robotics to replace human workers may be critical as a means of reducing operating costs and maintaining low prices. For Nordstrom, however, the most important technology may be artificial intelligence (AI) to enable sales associates with more effective service tools and information, all in an effort to justify higher prices.

Now my unfiltered response: I believe that AI will be the most profound technology of the next century in retail. It will fundamentally change every aspect of both the back and front end of retail. Everything from manufacturing processes, shipping, logistics, inventory management, staffing, training and customer experience will be directly and dramatically reshaped by virtue of AI. Consumers, too, will begin to operate with increasing help from AI-enabled systems, platforms and apps. Just as we rely on technology like GPS to navigate from point A to B, we'll use AI technologies to similarly navigate our consumer lives.

Finally, let's also step beyond that. What must retailers understand about the future regardless of the latest tech?

STEPHENS: There are only two strategic choices available to retailers who wish to survive the coming decade. Either sell something no one else sells (which is increasingly difficult in a globalized economy) or sell what you sell in a way no one else does. This means breaking the script in your category, devising new and compelling experiences and reinventing how people buy what you sell.

In essence, the unique selling process you create becomes as much of a product as the product itself.