When the threat of the virus kept scores of retail locations temporarily closed, ordering items online became the go-to option for many consumers stuck at home.

Instantly, almost every item was sold and bought online — from fresh produce and toiletries to apparel and office equipment.

In a matter of weeks, the shift toward a more digital world accelerated. The pandemic pushed shoppers to spend a whopping $844 billion online between March 2020 to February this year, according to Adobe. In 2022, Adobe projects e-commerce spending to reach $1 trillion.

"Anything that could be sold on the internet had to be sold on the internet, and the things that people typically wouldn't have bought in pre-COVID time, all of a sudden, became something they had to buy online," said Jon Reily, president of Dentsu Commerce.

The widespread online activity has allowed retailers to gain access to a trove of information about their consumers' purchasing habits, which they use to personalize the user experience and possibly inform future merchandising decisions, experts say. Through various mediums, businesses acquire information about shoppers such as the store locations they prefer to shop at, the ads they watch and the products they like.

These benefits might soon be short-lived. Retailers will have to navigate new privacy regulations and updates that could potentially disrupt their ability to target and further develop relationships with consumers. Apple introduced new privacy protections earlier this year through the iOS 14.5 update, which requires apps to ask users' permission to track them, and Google said it plans to phase out third-party cookies in 2023.

Among those who've installed Apple's software update, for instance, the weekly rate of users allowing apps to track their online activity is only 17%, as of early July, according to Statista.

"As a result you had a lot of companies getting data that they didn't necessarily have before," Reily said of the e-commerce boom. "The tricky part is finding that sweet spot between the first-party data you have, the second-party data you can believe, the third-party data you can buy, and do all of that without creeping out the customer."

"I think that retailers are really, really scared of the incoming or impending cookie-pocalypse and the data deprecation stuff, but I think it's really important for them to remember that everything old is new again."

Fatemeh Khatibloo

Vice president and principal analyst at Forrester

Retailers will now have to focus on first-party data, experts said, which is information they collect directly from their consumers, as opposed to third-party data, information collected by a source that might not have a direct relation to the consumer whose data is being gathered.

Shifting from third-party to first-party data

When cross-site data, cookies and third-party data became readily available, experts said retailers placed first-party data on the backburner.

As a result, tracking changes by the likes of Google and Apple have been stoking fear among some retailers and marketers alike, Sudipta Dasmohapatra, professor of the practice and academic director for the masters in business analytics program at Georgetown University, said.

"I think there's a lot of discussions that's happening today among retailers and among marketers," Dasmohapatra said. "But I do think that if they are savvy, they are already practicing how we can still generate more information from the customers in the right way, providing them with more of the privacy information that they are seeking and still make it work."

Collecting first-party data is expected to be a high priority for 88% of marketers in 2021, according to Merkle's recent Customer Engagement Report. That's likely directly linked to the liquidation of third-party cookies, changes to Apple's App Tracking Transparency, and government regulations like the California Consumer Privacy Act and California's Prop 24 that are looming over companies.

Despite the tension around the topic of data restrictions, first-party data collection has plenty of potential, said Fatemeh Khatibloo, vice president and principal analyst at Forrester.

"I think that retailers are really, really scared of the incoming or impending cookie-pocalypse and the data deprecation stuff, but I think it's really important for them to remember that everything old is new again," she said. "When they think about the opportunity that retailers have to build customer engagement, they're so much better positioned to do so than so many other verticals. And if they move away from the fear of losing access to data and move into what is the right data that we need to meet customer needs, they have tremendous opportunity."

While large and established brands can easily collect first-party data from their army of loyal consumers, apps and their advertisers (specifically small direct-to-consumer brands) are among the most vulnerable players in the data depreciation phenomenon, experts said. For DTC brands, advertising on social media sites like Facebook and Instagram remains an essential part of their customer acquisition strategies.

"Is it harder for a mom-and-pop shop to build a first-party data set? Yes, probably, not because it's impossible or not because their customers aren't willing to give them the data, but because it might be harder for them to manage that data," Khatibloo said. "They might not have enough data to be able to really build a model again, and to some degree, how much do they really want to invest in that kind of expense?"

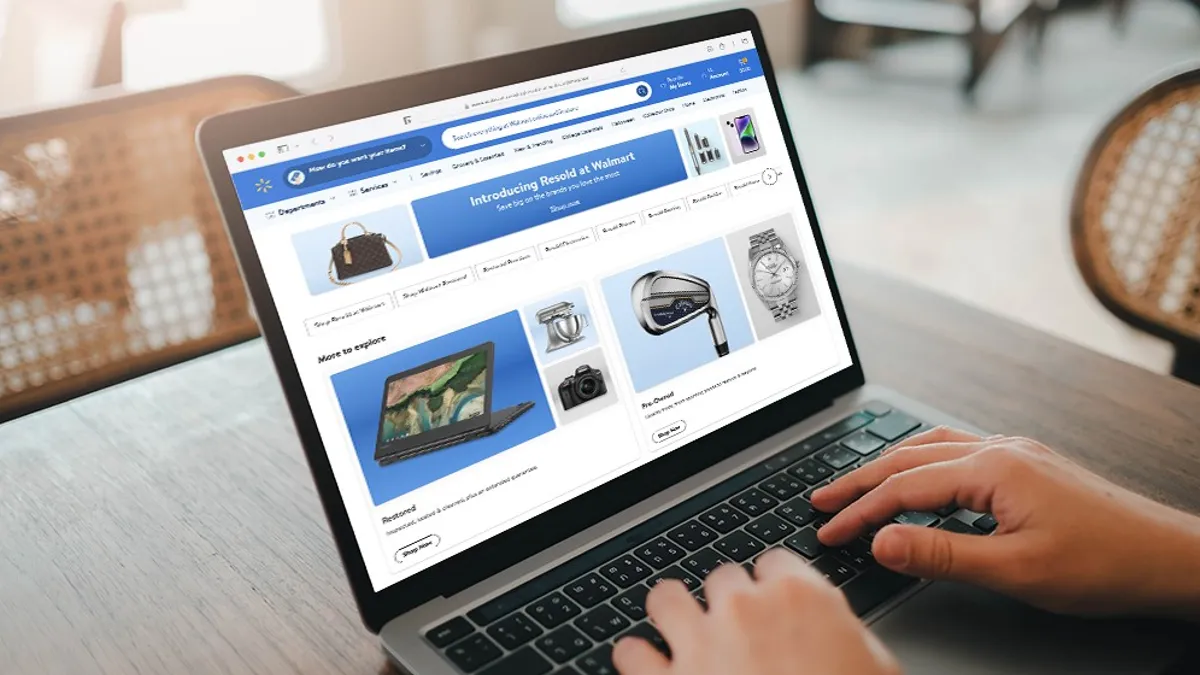

In comparison, companies like Amazon and Walmart have built an ecosystem of in-house businesses designed not only to win more of consumers' wallets but also to collect the data that enables them to scale their businesses.

Regardless of how small a business is, first-party data isn't necessarily impossible to acquire, Khatibloo said. When it comes to e-commerce and pure-play companies, "by necessity, you are collecting lots of first-party data, you already know what people are looking at on your website, you already know what they're ordering and you have their mailing address."

Then there's the existence of zero-party data, which is when consumers are given the chance to tell retailers what they are interested in or how often they want to hear from retailers, Khatibloo said. Some DTC and big-box retailers already utilize this to personalize their customers' shopping experience and it can come in the form of personality quizzes, a preference center or questionnaires.

"This idea of zero-party data, letting consumers tell you what they're interested in, what they want to hear about is incredibly valuable," Khatibloo said. "It can be done in these micro experiences, or it can be done as a profile page on a website."

Bargaining for consumer data

As retailers adapt to leaning more on first-party data, it's important to understand what customers are comfortable with and how best to reach them.

"There is definitely some degree of trust between consumers and retailers, and a willingness to exchange value if both sides are getting something."

Hilding Anderson

Head of strategy for retail North America at Publicis Sapient

Consumers have a complex relationship with tracking and data sharing but, in some instances, they aren't as stingy with their personal information as others might think. Some consumers are willing to trade personal information for perks — that includes discounts, personalization and better customer experience, according to Hilding Anderson, head of strategy for retail North America at Publicis Sapient.

More than half (54%) of shoppers surveyed said they are comfortable or very comfortable giving retailers their personal data if it means getting a good deal, according to a June survey from Publicis Sapient. Consumers were the most willing to share their contact information (40%), loyalty program memberships (38%), preferences (34%), purchase history (31%) and demographic information (31%) in exchange for the lowest price, the survey indicated.

"We do this every day with credit card companies, banking organizations, even in grocery stores with loyalty programs. It's part of the equation of that exchange of value," Anderson said. "There is definitely some degree of trust between consumers and retailers, and a willingness to exchange value if both sides are getting something."

As opposed to ad targeting firms, retailers are in a much more trusted position, he said. Whenever shoppers make a purchase or sign up for memberships, there is some understanding that retailers will have a record of that transaction as part of that value exchange.

"Understanding your customers, why they're shopping with you, what they are looking for, and how do you match what they're looking for with what you have to sell is fundamentally what retail is all about," Anderson said. "The more data that you have, the more accurate and better the experience you can create for your customers."

Some consumers feel excited about the incentives that come with their relationship with retailers, including early access to products and sales, virtual wallets and acquiring points, experts said. This allows retailers to aggregate consumer information and form a comprehensive profile about a consumer.

Retailers then draw insight from this data to predict demand, price products accordingly and adjust promotions, Georgetown University's Dasmohapatra said.

And the end goal? It's to move consumers toward making a purchase, she said.

Still, it's essential for retailers to resist asking their consumers for too much information, Publicis Sapient's survey indicates. Credit card activity (6%), homeownership information (12%) and income level (14%) are at the bottom of the list of information consumers are likely to share with retailers even in exchange for discounts.

"What is really required is for the customer to feel that the company cares about them. I think that's the biggest thing, what kind of relationship the customers have with that particular company," Dasmohapatra said. "I think there's something to be said about how companies really maintain that relationship with their consumers over time and how they are engaging them in the right way."

The 'fine line between delight and creepy'

When it comes down to it, retailers need to be more transparent about how they are using customer data in order to gain trust, experts agreed. Though the ethical concerns around data acquisition may not entirely disappear, they can certainly be lessened.

Companies will have to rethink their method of acquiring data sooner rather than later, though.

California leads the country in enacting consumer privacy laws, experts claim. In 2018, state legislatures passed the California Consumer Privacy Act which gives consumers the authority to request data collection firms not to sell their data. California's Prop 24, which voters approved last year, addresses several issues in the existing privacy regulation.

"Laws can be radically different from state to state," Dentsu Commerce's Reily said. "Once things quiet down again, I think you can see a renewed push to limit the amount of information that companies can hold on you, the way they do now, virtually forever."

The EU General Data Protection Regulation, which Reily said is the "gold standard" among regulation laws, puts harsh fines of up to tens of millions of euros on companies who violate privacy and security standards upon taking effect in 2018.

Several brands in the U.S. follow European standards or the strictest standard in the country even though they aren't required because it benefits them if they ever plan on conducting business in well-regulated areas, Reily said. And as to how the consumer data protection changes and laws will affect retail operations: "We're writing that story right now, nobody knows the answer to that."

"If you get into a relationship with a customer or a company where you feel they're being too pushy, you'll go somewhere else," Reily said. "When I was at Amazon, we used to jokingly say, 'find that fine line between delight and creepy'— and that's the tricky part."