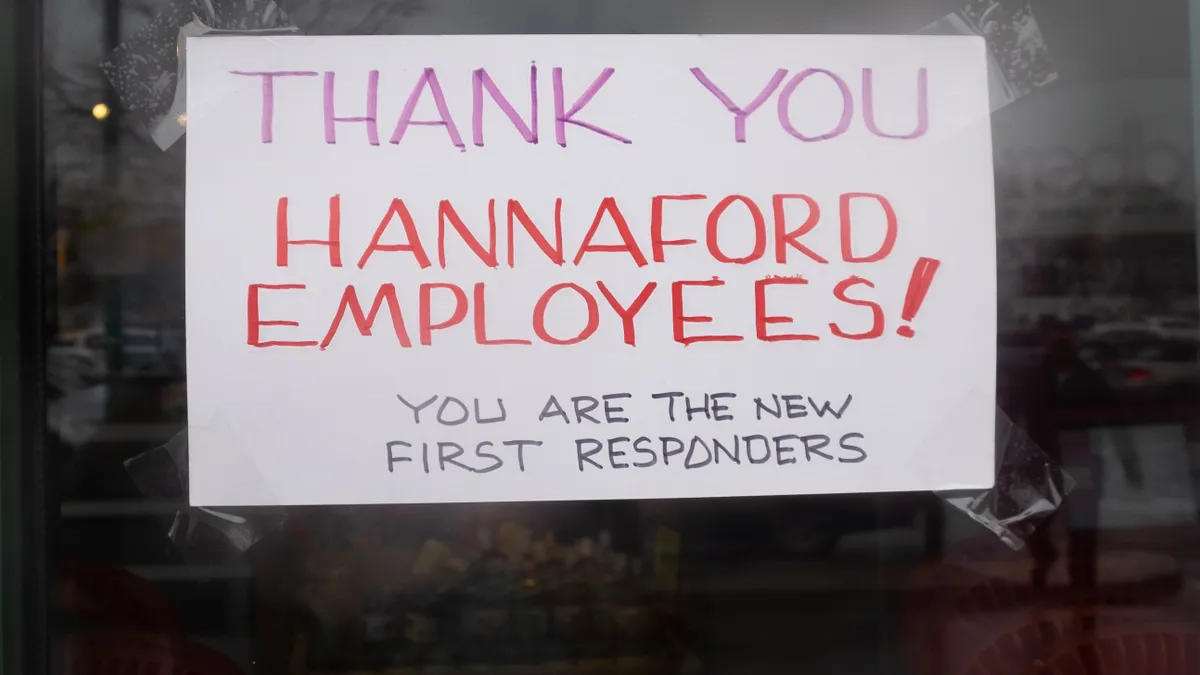

It took a pandemic to remind the world how essential retail workers are. To state the obvious, stores don't open without the workers there to operate them. Navigating customer needs and store operations can be difficult work in normal times, and this year has been everything but normal. Workers at open stores amid the pandemic were given the title of "heroes," while others faced furloughs amid mass closures among nonessential stores.

The retail trade lost 2.1 million jobs in April, according to a recent U.S. Census report. "Retail workers have been among the hardest hit during the pandemic for many reasons including stay-at-home orders that threaten their earnings," D. Augustus Anderson and Lynda Laughlin, authors of the Census report, wrote. "For those that continued to work, many were in work environments that put them in direct contact with others, increasing their likelihood of infection."

Their jobs were difficult and their lives were in flux long before COVID-19 reached the U.S., as technological and structural shifts disrupted the industry and wreaked havoc on key sectors.

As the research paper "Change and Uncertainty, Not Apocalypse: Technological Change and Store-Based Retail" notes, retail jobs are largely "relatively low-paid occupations, with high turnover, low formal credential requirements, and limited presence of unions." As e-commerce, big box and discounter competition eat into the markets of department stores and other mainly mall-based retailers, workers have suffered following stores closures and bankruptcies.

Along with structural shifts in the industry, the authors of the new paper, Françoise Carré, research director for the Center for Social Policy at the University of Massachusetts Boston, and Chris Tilly, professor of urban planning and sociology at UCLA, take a deep look at how workers have been affected by technological changes to the industry.

"We knew there were things going on but had no clue of how much we, as customers, and retail workers were already being scrutinized by cameras and sensors and so on."

Chris Tilly

Professor of Urban Planning and Sociology, UCLA

Behind or alongside every retail technology is a retail worker that has to use it, teach a customer to use it, fix it, feed it data, watch over it or live with being watched over by the technology, or ultimately even be replaced by that technology.

Technology covers everything in retail operations today from e-commerce to inventory management to pricing technologies, and much, much more. Its impact on the humans operating the stores is just as expansive. As one example, Tilly said in interview he was surprised by the extent that new technologies allow for surveillance of a store's occupants. "We knew there were things going on but had no clue of how much we, as customers, and retail workers were already being scrutinized by cameras and sensors and so on," Tilly said.

Other technologies that give employees windows into store operations or provide channels of consumer engagement also change the jobs of workers, for the worse in some cases. Carré said there is risk of workers "losing mind space through multiple interactions, through multiple tools, while trying to have an interaction with a customer." That in turn can leave store associates "feeling like there's no break, not time to collect thoughts," she added. And these shifts come at a time when stores are trying to prove their value to customers, including through personalized and attentive customer service.

Their paper looks primarily at the impact on workers of inventory management, checkout, e-commerce customer engagement and worker management technologies. In many cases, a range of outcomes is possible, from freeing workers up from repetitive tasks like searching for stock-outs and setting prices to interact more with customer, to creating more controlled and coercive work environments.

And of course, technology carries the potential to eliminate jobs, though Tilly and Carré reject the idea that e-commerce will swallow store retail and cause an apocalypse for retail jobs. That is a matter of ongoing debate in and around retail. A white paper by Euler Hermes, a credit insurance company, found based on Bureau of Labor Statistics data that discretionary retail has shed 670,000 net jobs, 9.6% of the total, since 2008, a loss of jobs that tracks with e-commerce penetration. The Euler Hermes report also found that four and a half jobs are lost at traditional retailers for every one that is created by e-commerce.

E-commerce isn't the only job threat. Among other technologies, Tilly and Carré write that self-checkout and decentralized checkout could eliminate cashier jobs, and even worker management systems carry the potential of making some routine decisions and eliminating the need for some management jobs. All of that said, the authors note that adoption is uneven and doesn't follow a straight line. In conversation, they both also noted the financial and organizational impediments to integrating more technology.

Where job losses occur can have outsized impact on different groups of people, as Tilly and Carré note in their paper. Losses among general merchandise retailing has racial implications given its diversity. They also write, "The bleeding of department stores stirs concern because the general merchandise sector employs far higher percentages of women and people of color than retail as a whole, and far more than e-commerce, whose workforce is considerably whiter and more male than retail overall."

COVID-19 has put technological adoption among retailers in the spotlight. Online sales have surged, with triple digit growth for some of the biggest players. Contactless checkout is in demand like never before. BOPIS and curbside pickup options have been rolled out or expanded at breakneck speeds. Adoption is likely to continue, even if not in a straight line.

And it will change jobs. Despite optimism among executives and tech providers that new tools will free workers up and allow them to develop other skills, historically retailers have tended toward low-cost and high monitoring of retail workers while adding tasks to their plates, according to Tilly and Carré. They note that "for decades, the bulk of retailers have not diverged from the habit of treating labor as a short-term adjustment variable, and labor costs as a primary cost liability."