Lego's newest store in New York is populated by a host of massive 3D brick models: A big yellow taxi cab, various New York landmarks and a centerpiece "Tree of Discovery." The last model alone is composed of over 880,000 Legos.

In addition to a lot of physical Lego bricks, the store is also centered on building out digital experiences for customers to engage with. Those include a "minifigure factory" where shoppers can design their own minifigure; an AR "brick lab" that involves creating a physical Lego model and rendering it into a digital experience; and a storytelling table aimed at older kids and adults where they can check out Lego prototypes and how the design process works.

"Things like the brick lab, the marketing content, the play experiences, the models that we feature will change on a regular basis," Simone Sweeney, vice president of global retail development for the Lego Group, said in an interview. "And those respond to the seasonality of the store, so in the holiday period, we'll ensure that we have something suitably festive. We do things for Halloween, for our product launches, for core events like, for example, celebrating Star Wars' May the Fourth, or Black Friday, Cyber Monday. So we will be changing the theme regularly."

It's a new format Lego's been working on for two years, and the company plans to expand certain elements of the concept to more than 100 stores globally in the next year.

Camp, which refers to itself as a "family experience company," has similar (if significantly smaller scale) plans. The company, which opened its first store in 2018, has scaled up to six locations and aims to be a national chain eventually. Its stores are positioned to be places families can go to hang out, with a clearly defined "play" area in addition to a more shopping-focused spot near the entrance. The play experiences operate on rotating themes, like "travel" or "cooking," similar to the way Rachel Shechtman ran Story before its Macy's acquisition (Shechtman is a Camp board member).

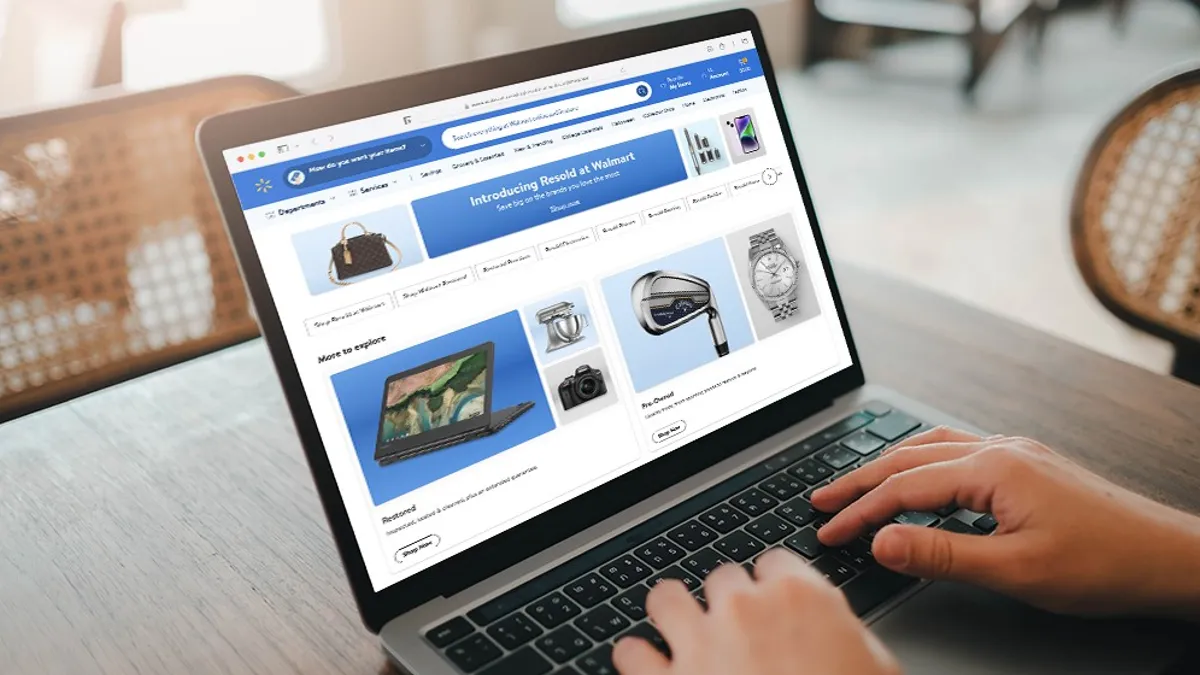

It's a far cry from the aisles-of-toys approach that big-box player Toys R Us took before its liquidation in 2018. Today, stores that sell toys usually operate in one of a few different ways, according to Michael Brown, partner and retail lead for the Americas at Kearney: as points of commerce, as store experience centers or as brand-building locations. Lego is one of the latter, someone like Walmart occupies the first category and Camp is an experience center.

"There's a lot of room for that. There are places where parents are looking for things to do with their children on the weekends, in the evenings, and help them have new learning experiences. And that's a role that I think Camp plays," Brown said.

Amazon, Target and Walmart are occupying the more transactional toy space, with low prices, easy delivery and other convenient options. No one so far has filled the Toys R Us-shaped hole in the market with another specialty big-box store — it's been a mix of various retailers picking up the leftover market share — and some believe no one ever will.

The seasonal nature of toys means it's unlikely there would ever be another specialty retailer in the category, said Linda Bolton Weiser, managing director at D.A. Davidson & Co. "They can't survive profitably in the rest of the year because so much of the sales are in one particular period of time. The Targets and Walmarts of the world can use toys as a loss leader. They can promote them heavily. They can even sell them with no profit attached to the toys just to get store traffic during the holidays. But a Toys R Us or any other type of specialty retailer that only does toys cannot do that, or they will not operate profitably."

The new toy stores aren't toy stores

Experiential retail is the name of the game for Lego and Camp, despite a pandemic that has challenged high-touch concepts for over a year. In many ways, it makes sense for the toy category, which is centered around the basic idea of children playing. Even Toys R Us had some experiential elements, including birthday parties and interactions with Geoffrey the Giraffe, Weiser said.

The retailer's massive stores were a hindrance to its success, though. And separating Babies R Us into its own stores meant losing another method of keeping Toys R Us locations profitable, according to Brown. Except for the holidays, consumers got used to going to one-stop shops like Walmart and Target for their toy needs, and the Toys R Us experience wasn't strong enough to draw in shoppers.

"It's always been at the heart of the best toy stores," Brown said of experiential retail, pointing to FAO Schwartz and its iconic dance piano as an example. "Toys R Us also could have done a better job with that. I don't think it was as experiential as it could be. It was wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling toys, which was a fantastic business three months out of the year. The rest of the year, the store suffered because they didn't really do enough to bring people into the stores. They didn't have a place where they had all those basketball hoops that you wouldn't get yelled at for taking shots with or those types of things."

One of the final nails in the coffin was the rise of e-commerce and the fact that kids don't play with toys as much as they used to, thanks to electronics and other digital games and devices. That balance between physical and digital play is something Lego is trying to solve with its new format.

In addition to selling wholesale, the brand has 736 stores in 50 countries, and all stores will eventually reflect Lego's newest format in some capacity, Sweeney said. Smaller stores might only have a selection of the features, while flagships will likely align closely with the New York location. Digital experiences will be available throughout the store, alongside more traditional physical play opportunities, like store associate-led scavenger hunts through the store or photo opportunities.

"Play remains at the absolute core of what we do. Our stores are there as a way to immerse our shoppers and our guests in an amazing world of Lego bricks, where they can get hands-on, where they can play, where they can let their imaginations run wild," Sweeney said. "So we will have lots of play experiences."

Camp and Lego aren't exact replacements for something like Toys R Us. But they may point to the future of the toy experience going forward. Unlike Toys R Us, which operated out of large, stand-alone stores, Camp and Lego have a different real estate strategy. Both have stores on New York's 5th Avenue, and Brown expects both to continue opening stores in high-traffic areas like popular malls and shopping streets.

Tiffany Markofsky, co-founder and chief marketing officer of Camp, said the company is also looking for communities with a high density of young families, for example, Columbus Circle, which is its most recent store location in New York. The company also has a store in Hudson Yards, the buzzy mall that opened about a year before the pandemic hit the U.S.

"We're becoming a little bit like an entertainment company. We are a media company now that's creating a ton of content and doing so many different things," Markofsky said. "While at our core, we are sort of a toy retailer — that's like 80% of the things that we sell and we sell thousands and thousands of products — it is tough, just because there is nothing [like it] that exists."

Camp's stores have a general store section dubbed the "Canteen," with a cafe and an ice cream shop (it features craft coffee and upscale ice cream brand Jeni's to cater to adults). There's general merchandise in this area, like books, candles and some toys — something for both parents and children, according to Markofsky — and then a "magic door" that leads kids to the themed play area, with appropriate merchandise scattered throughout.

Activities in the stores range from arts and crafts to storytime, magic shows and music classes. Markofsky wants it to be a place families come for birthday parties or just to find something to do on a Saturday. For that reason, it's trying to cater more to adults as well, not only by offering some adult-appropriate merchandise for something like a dinner party but also by making stores aesthetically pleasing and offering certain services aimed at parents.

"We had drop off, so parents could go on their night out and leave their kids at Camp. We'd have these sleepovers at Camp, but just in the evening, and they would pick their kids up," Markofsky said of a pre-pandemic service. "And every now and then, we would also have little evening classes or mixers or things for parents."

For Camp, the experience is critical, because it doesn't command a brand like Lego, Brown noted. Lego is so well known that kids will ask for its products specifically, but Camp's value proposition is incredibly reliant on the store experience. Brown likens it in some ways to a store like Build-A-Bear, which is equally about the bear and about creating the bear yourself.

A top-notch in-store experience doesn't solve all of the problems of a toy store, though. A response to digital also has to be factored in.

Bringing digital indoors

Camp didn't have much of an e-commerce presence before the pandemic forced it to. Now, it refers to its kids-focused e-commerce site as "experiential e-comm." There's editorial content for families looking for things to do, and there's a guided, interactive shopping experience for children, designed to let them pick out gifts for themselves, a friend or an adult.

Parents decide the dollar value of the gift and answer questions about who the child is shopping for, as well as address and other basics. Kids then answer questions about what the person they're shopping for likes and the site displays personalized recommendations in response, while a cartoon bear helps guide them through picking out a gift.

"It teaches kids about the responsibility of gifting. It gives them the gratification that comes along with gifting, as opposed to me buying a Father's Day present for my husband and having my daughter sign the card," Markofsky said. "It helps parents, which is like a total pain point. Every week, my daughter's like, 'Oh, it's so-and-so's birthday in my class.' She could now [get the gift]. And it also solves the problem of: Kids don't use cash anymore."

Lego's site specifies that kids must have a parent or guardian present to shop online, but there is also a "play zone" where children can look at Lego sets, play games and watch videos.

Whether or not kids can actually purchase products, marketing to them is increasingly important, according to Weiser.

"Kids are being engaged online with content increasingly and that's attracting kids to different brands and different products," Weiser said. "I think that when customers go into the store, it's probably less of a decision making process in the store. They've already decided what they want based on digital interactions online. That's a really big difference versus several years ago."

Even before the pandemic, toys was one of the highest categories purchased online, Weiser said, at 25%. The pandemic accelerated that shift even further. Build-A-Bear, another experience-based toy seller, saw over 20% online market growth in the early months of the pandemic, according to 1010data. And digital is increasingly an expected part of any shopping process.

In Lego's newest store, the approach to digital comes in the form of making space for both physical and digital play experiences. The company's brick lab is a $15 bookable "experience" where kids can spend 20 minutes playing through an augmented reality-based Lego story. The walls, floors and ceilings all project an animated story, and whatever the child makes with Legos is scanned into the virtual experience where it can be engaged with through touch screens.

"It's really fun. It's really, really different," Sweeney said. "And it's complemented by a new cast of special characters that have been created for this immersive play experience that acts as your narrator and kind of send you on a mission."

The store also has something called "Lego Expressions," where a Lego character on a screen mimics customers' facial expressions, and "Lego Wave," a screen that is placed at the checkout line where customers can interact with Lego's Statue of Liberty character while waiting to pay. Other experiences, like the brick lab, come with a cost attached.

Shoppers can create a personalized Lego version of themselves to bring home or a Lego mosaic portrait. (The mosaic costs $130 and requires booking.)

Even outside of the toy space, retailers are increasingly creating concepts that acknowledge digital. Take, for example, some of Nike's newest formats, which are so centered on the company's app that it's a disadvantage if consumers don't have it. Whether it's in stores or directly through the e-commerce site, toy sellers can't ignore digital, even if their target audience is under 10.

"Kids are digitally savvy, and it's just one more place that brands can engage them," Brown said. "Because that's where it's all happening in their world right now."