Editor's note: This article is part of a series on sustainability. You can find the whole package at our landing page.

In a panel discussion early last year, Ron Jarvis, chief sustainability officer at The Home Depot, spoke a deep truth about all of the retailers pursuing sustainability: that there’s really no such thing as an environmentally friendly company.

“People ask me all the time, ‘Is this an environmentally friendly product?’ And I go, ‘No.’ Unless you’re an organic garden grower that has your garden by the river, and you deliver all your products in a wagon and a buggy, then you’re not environmentally friendly,” Jarvis said at the time. “Everything we do has an environmental impact. There’s risk across the board in everything, whether it’s carbon emissions, chemical exposure, deforestation — all of those are risks. We look at those and we monitor and we say, ‘Which ones are acceptable risk? Which ones could hurt the greater good? Which ones could hurt society?’ There’s risk across the board. And they all keep me up at night.”

Jarvis isn’t the only one pondering the existential questions around retail and its impact on the environment. Asked if running a retail business is antithetical to sustainability, Mike Cangi, the co-founder and brand director of sustainable apparel company United By Blue, said it’s a “very valid and fair” question.

“How do you balance the negative impacts that any business has ... with the desire to leave the world better than founded and to build an actually sustainable business?”

That’s something Cangi and his company think through often. To him, United By Blue and other sustainably-minded brands are there to serve customers who aren’t going to completely swear off buying new products for the sake of the environment. And Cangi guesses “the vast majority of people” fall into that category.

After all, the desire for newness is part of why retail exists at all. Consumers like buying new products, and fashion trends aren’t stagnant laws for shoppers to abide by — they’re ever-changing. So, Cangi argues, if consumers are going to buy products anyway, then maybe United By Blue is doing good by giving them a more environmentally friendly option.

“By putting out a better alternative, is that at the end of the day justification for making that product?” Cangi said. “As opposed to deciding that, ‘OK, no, we're not going to sell it’? Because if customers are out there that are going to buy the product that is having a worse impact, then it allows us to help push things forward.”

Acknowledging that consumerism is a part of life, how can retailers pursue meaningful mitigation against the carbon emissions and waste they create? At what point should retailers stop prioritizing growing their businesses if it ultimately means more damage to the environment? And what should that type of calculus look like?

“I love those types of questions,” Cangi said. “Those are the big existential questions that I wish kept more people up at night.”

‘We are in a capitalist world’

Retail might never be an environmentally friendly industry, but we as a society are also unlikely to ever do away with retail. Pursuing sustainability, then, requires retailers to re-examine how they operate and in some ways, reconsider the core purpose of a business: making money.

Listen to any earnings call and retail executives will discuss their path to growth. The promise of fast growth has led to skyscraper-high valuations for some of retail’s youngest players, including fast fashion company Shein, which has become known for its heavy environmental impact. Thinking sustainably in the long run might mean jettisoning growth, or at least de-prioritizing it.

Catherine Chevauché, chairwoman of a technical committee on the circular economy within the International Organization for Standardization, is leading an effort to create a set of standards encompassing issues like how to move from a linear to a circular business model and what key performance indicators businesses should watch to judge if they are making progress.

“To be circular means that you will have to use less material to be able to slow the loop, to narrow the loop and to close the loop,” Chevauché said. “So what does it mean? The question is growth and do we have to de-growth? Maybe.”

Chevauché also works for water and waste energy management company Veolia, which is talking about how to emphasize selling quality over quantity.

“Maybe it could be the same for retailers … to be able to have a profitable business model but not based on growth,” Chevauché said. “But it’s not an easy question because up to now, we are in a capitalist world and we are based on that growth.”

"Inherently, we're doing harm to the environment with a lot of business decisions that we make, even though we can do them better.”

Ann Cantrell

Associate professor in the fashion business management department at the Fashion Institute of Technology

Ann Cantrell, an associate professor in the fashion business management department at the Fashion Institute of Technology, agreed that the industry needs to “reassess what success means” in the long term, but added that is unlikely to happen anytime soon. Cantrell also runs an urban general store in Brooklyn, New York, called Annie’s Blue Ribbon General Store, and is working through the same challenges in how to run a business positively.

“On one hand, we are businesses and have to make money, but we can do so in a way that is not just looking at the profitability of the business as the end goal, but also what we say is the triple bottom line: with people and prosperity in there as well,” Cantrell said. “Prosperity for all, too, and not just profit for some. So a better, more mindful approach. But inherently, we're doing harm to the environment with a lot of business decisions that we make, even though we can do them better.”

To ensure they’re doing things better, some businesses are self-regulating by becoming B Corps or achieving Climate Neutral certifications, which prove that their businesses adhere to a certain set of standards. But that’s a path that only retailers dedicated to sustainability and ethical manufacturing will follow — to move the whole industry forward, legislation might be needed.

As one possible solution, Cantrell pointed to the Fashion Sustainability and Social Accountability Act in New York, which if enacted would require retailers that make over $100 million in revenue to map their supply chains and release impact reduction targets, among other things. Businesses that don’t comply would be fined. The Fashioning Accountability and Building Real Institutional Change Act, a separate bill that was introduced to the senate recently, would increase garment workers’ wages and hold retailers accountable if they work with factories that don’t pay minimum wage. It would also incentivize businesses to manufacture in the U.S.

“There's a business decision there, that if we're not following these new legislations, which hopefully get passed … then there would be ramifications for that,” Cantrell said. “That's the only way I really see businesses changing on that larger scale.”

Mark Sumner, a lecturer in sustainability at the University of Leeds, sees the business case for sustainability catching on, not just thanks to legislation, but also as executives are pressured by key stakeholders.

“I've spoken to a number of executives where they say, ‘You know what, I'm not really into sustainability — don't really get it. But it makes sense for my business to start positioning itself in that way,’” Sumner said. “So we're sort of detaching that moral or ethical decision making to much more economic decision making.”

The goal isn’t to stop retailers completely from growing: Businesses are a key piece of society that support jobs and provide other benefits, Sumner said. The goal, rather, is to find a way for businesses to remain successful without the “continuous volume growth.” At least that’s the case in the U.S.

“For developing countries, it's not the same question,” Chevauché said. “The question is more how to grow, but in a more sustainable way — and not to apply what Western countries did.”

Keep doing business, but do it better

As a result of the climate crisis, retail is facing a future that will include higher prices across the board: more expensive cotton, more expensive energy and less access to labor are just a few of the costs of the crisis, according to Sumner. In short, running a business is set to get a lot more expensive, and those that don’t address these challenges now may not survive long enough to make up for it.

“That's a very dark view of the future, but it's a very plausible one if we carry on as usual,” Sumner said.

Retailers aren’t without options to address some of these challenges, but doing business better often means making things harder in the short term. And in many ways, it means changing the very foundations that retailers built their businesses on.

“The circular economy deeply questions our way of consuming, our way of producing that we have in Western countries, and it's not easy to change,” Chevauché said. “We know that we have to change because we all know about climate change. … But even if we know, we do not still apply the solution. Why? I don't know — maybe it's because we are human and it's easier to go on like that until we have a real problem. It's always difficult to question ourselves and to change.”

But change, in a lot of different areas, is what’s required, starting with the most basic part of retail: the materials used to make products. That conversation, perhaps, begins with cotton — one of retail’s principal materials. Cotton production uses 23% of the world’s insecticides and in 2020, less than 1% of cotton was recycled, according to McKinsey’s The State of Fashion 2022 report.

There are efforts to make growing the crop more sustainable. For example organizations like Better Cotton focus on helping farmers grow cotton while improving soil health and greenhouse gas emissions. According to Sumner, reducing the use of fertilizer and pesticides in cotton production can eventually make cotton cheaper, but it comes at the tradeoff of increased labor for farmers.

The pursuit of new materials, therefore, has come to the forefront as retailers look for a more sustainable way to do business. Take Allbirds, for example: The brand was founded with the goal of finding a more environmentally friendly way to make shoes. That meant using materials like wool, tree and sugarcane, which were not the common choice for footwear. The company’s new sustainability goals now include pursuing regenerative agriculture for its farming of those materials, and investing in new alternative materials.

Mylo — a leather-like material made from mycelium, the branching underground structure of mushrooms — has become a hot investment area for retailers as diverse as Lululemon and Stella McCartney. While that sort of innovation is a promising solution, those new fibers have to be scaled up enough that they can meaningfully replace existing materials — and whether or not they remain more sustainable at that scale is unclear.

“We need to explore that to make sure that what we don't do is walk blindly into another environmental issue by looking at these new materials,” Sumner said. Cotton is also hard to replace, as the industry already has the technology to produce it on a large scale. “So one of the areas that I think is going to be key in terms of focusing is less about new materials, but actually thinking about how we can continue to use the materials we have and doing it in a much more sustainable way.”

In fact, there’s a lot of work retailers could be doing to improve the sustainability of their businesses without innovating new materials. Cantrell noted that a good starting point for retailers is tracing their products’ entire supply chain and building relationships with each supplier along the way, “so we feel confident and comfortable with who we’re doing business with.”

She also highlighted the opportunities in making products easier to repair and more durable so they don’t need to be replaced as frequently. Patagonia, she noted, redesigned its jackets after the company realized it cost more money to replace a zipper than to buy a new jacket.

Retailers can also take a critical eye to their product assortment and stop selling products that rely heavily on chemicals in the production process, Chevauché said, or pilot refillable container programs, similar to what The Body Shop is doing with some of its personal care offerings. There are endless ways to chip away at the environmental impact a business causes, but ensuring the solutions are actually more sustainable than the status quo is the hard part.

When it comes to recycling and reusing materials, for example, many apparel items are a blend of several different fibers, which makes separating out individual materials to reuse challenging, according to Sumner. Some technologies are beginning to address this issue, Sumner said, but it remains a problem for the industry as it tries to tackle the waste it creates.

Behind every would-be solution is a host of questions retailers need to answer, the foremost of which is as simple and complex as: Is this actually going to make things better?

'It's got to look good, and people have to want it'

As much as retailers can do to improve their own businesses, to limit the growth mindset they instinctively have, they are also up against an equally challenging force: the consumer. Retailers hear time and time again that shoppers are interested in sustainability — and shoppers tell researchers time and time again that they want to support environmentally friendly brands.

And yet, consumers continue to consume. Gen Z, a generation that consistently espouses its interest in saving the environment, has also given rise to fast-fashion retailers like Shein.

“It's really easy for many of us to sort of point the finger at Gen Z, for example, and say, ‘Listen, you guys know better than anyone else the issues of sustainability, you're the ones that are going to suffer more than any other generation, currently. So why are you doing these things?’” Sumner said. “And actually, their response could be, ‘Well, you did it when you were my age. So why can't I do it?’”

Consuming has become a part of human nature. And even for consumers that care about sustainability, appearance and price are ever-present considerations. Shoppers choose what to buy not just because they need something new or because they support a particular brand, but because they like it. Fashion is part of what society uses to define itself. Or, as Sumner puts it, fashion is “the most powerful, nonverbal communication device that we will use.”

As a result, retailers have the challenge of not only revamping their business practices to support a more sustainable way of doing business, but also not losing sight of what really matters to customers.

“It's got to look good, and people have to want it,” as Cantrell put it.

A study last October from pricing consultancy Simon-Kucher & Partners found that about a third of consumers were willing to pay more for sustainable products. At the same time, 60% of participants listed sustainability as an important purchase criteria. The gap between those numbers suggests that a majority of shoppers care about buying from sustainable brands, but only a minority are willing to pay for it.

“When I was working in the industry, we absolutely focused on sustainability. But we did not compromise quality, fit, style, and affordability,” Sumner said. “Because we knew that those things were, in the consumer’s brain, much more important than sustainability. And I would argue that, that is still the case.”

Consumer behavior is a force that retailers have to work with — there isn’t an option to ignore it. But retailers can work within it to raise awareness and education around the environment, and try to push consumers toward new behaviors. Cantrell pointed to Everlane, which displays the costs that go into pricing its products online, as a good example of a business educating shoppers on the impact of their choices.

"There is a story and a consideration at every level."

Ann Cantrell

Associate professor in the fashion business management department at the Fashion Institute of Technology

Rather than using marketing to push only sales or new purchases, retailers could also use those channels to highlight how new items work well with a brand’s older products, Cantrell said, or refocus their marketing efforts around other community-building activities to help people “rethink what makes them happy.”

As with everything else about tackling sustainability, though, how to engage with consumers is not straightforward. The complexity of the climate crisis, the uncertainty around the correct action to take, can make people feel overwhelmed and “paralyzed,” according to Sumner.

“You can't just say, ‘shop at this store’ or ‘produce with this company’ or ‘use this material,’” Cantrell said. “There is a story and a consideration at every level.”

Likewise, Cantrell noted that companies are afraid of being called out for greenwashing. And those sentiments impact how businesses are able to react to the crisis. Sumner recalled a recent conversation with an organization about sustainability where senior management said its employees simply didn’t know “what the right thing is to do.”

“I think this is one of the really big challenges — for the fashion industry in particular, because it is so complex,” Sumner said. “How do we simplify and get people to think about how they can move forward and make big impacts, rather than focusing on the small things?”

Reducing the retail industry’s environmental impact is a long and winding journey. In 2016, according to a recent McKinsey article, just a “handful” of retailers had science-based targets to reduce carbon emissions. Now, the research firm counts more than 65 global retailers, with the number “more than doubling each year.”

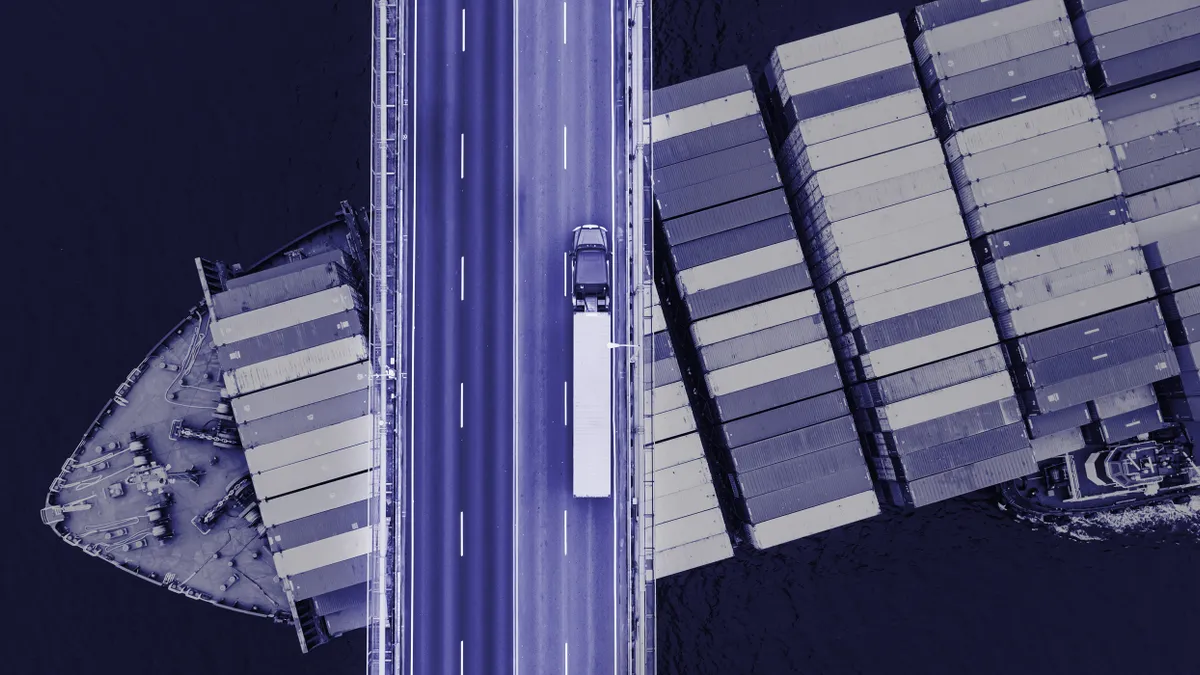

But even with retailers beginning to tackle their carbon footprint more purposefully, 80% of emissions can come from outside sources like suppliers and transportation, which aren’t directly in retailers’ control. That number rises to as much as 98% for home and fashion retailers.

So, can retailers truly be sustainable?

“If you are selling fast fashion, I would say ‘OK, no way,’” Chevauché said. “The water footprint, the greenhouse gasses footprint, the biodiversity footprint is not in your favor. But it's difficult to say to these kinds of people, ‘OK, stop your business. It's not a good one.’”

At their core, the concepts may be opposed to each other. But with a lot of work and significant transformation, retailers can perhaps be better than they are today.