What's in a name? Or maybe the question today is: How many dollars are in a name?

For Modell's Sporting Goods, or Pier 1, or Bealls, and scores of their peers, their names stand for decades of retailing history and customer relationships. Thousands of memories of being in stores scattered through time and demographics.

A name is a reputation. It can be tinged with nostalgia for an entire moment in commercial and social history. The Toys R Us, FAO Schwarz or Blockbuster brands can call up childhood memories for large swaths of entire generations.

There is a market for retail brand names that is more relevant than ever, as technology has helped define and support it, and many physical retailers face a financial reckoning.

Pier 1's intellectual property and e-commerce site sold for $31 million this year to Retail Ecommerce Ventures. That little-known firm, founded by digital marketing specialists, also acquired Modell's brand property this year out of bankruptcy for $3.6 million and last fall bought the Dressbarn IP from Ascena for an undisclosed amount.

REV is hardly alone in hunting for bargains in the retail graveyard. Authentic Brands Group, Sequential Brands and a host of others have been actively buying up IPs for sale in a year which could hit record levels of retail bankruptcies.

This isn't a new phenomenon, but it's not very old. "The notion that retail and consumer brands have value separate and apart from the enterprise really started to take hold in the prior economic cycle, in the run-up to the Great Recession," said David Peress, executive vice president at Hilco Streambank, which specializes in IP sales and disposition.

Peress said Jamie Salter, today Authentic Brands' CEO, was one of a handful of people pushing the model, along with William Sweedler, who today chairs Sequential Brands, and others. Supporting the bets on IP was the growth of e-commerce as a sales channel and the technology behind online stores.

"What technology did was it expanded the ability to go to market and efficiently target sectors that historically the only way you get there was you built a store," Peress said.

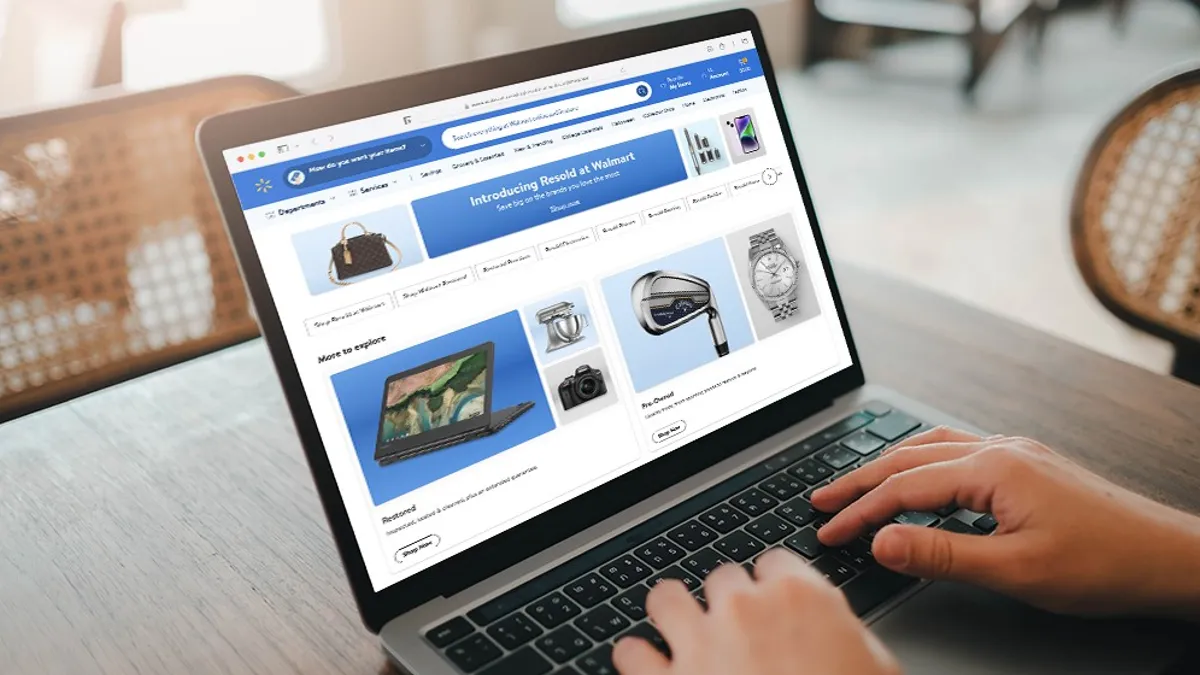

All of that has continued to accelerate, Peress notes, with tech services like Square and Shopify making it far easier to build out e-commerce operations. "So today, you can very quickly spin up an e-commerce site that has all you need to engage in commerce," Peress said. "Even a year ago that was much more difficult than it is today. It's given digital marketers the ability to get to the market more quickly, and more effectively."

Online is a crowded world. A brand gives the marketer distinction. "Think about how hard it is to build a brand in today's world," said Greg Portell, lead partner in the global consumer practice of consulting firm Kearney. "It's really difficult."

Building a brand takes time, resources and plenty of money. Buying one, especially out of bankruptcy, can be a quicker and cheaper path to online success. But brands alone won't make profit for their acquirers.

"The critical component to that is whether I'm going to use that name or not. The collection of brands simply to have a logo on a webpage is very shortsighted," Portell said. "If I'm planning on monetizing that brand and bringing new life to it, then it becomes incredibly valuable. Because building that brand up is really hard."

Rise of the asset-light brand

Intellectual property includes everything from the company's name and domain name to customer lists, data on what those customers bought, suppliers and all manner of other intangible aspects of a business.

The customer data alone could help propel the reborn brand. "It's that data that is so powerful to these advanced modern digital marketers," Peress said. "The more data they have, the more understanding of what you buy, where you buy it, at what promotional level you are incented to buy — the more they have, the more effective they can be to get you to buy stuff."

Generally, Peress said, well-managed email databases lose 1% to 2% of their customers through unsubscribing per year. After database transfers (through acquisitions), that usually doubles in the first year — to a still-very small number — and then returns to the historical attrition rate. In other words, not many customers are lost typically after an IP changes hands. "That speaks to the stickiness of customers and loyalty to the brand," Peress said.

Portell says that the name itself tends to be the valuable asset in an IP portfolio. "The challenge for companies that are buying consumer lists or customer lists from someone is, how portable is that target base ... how reusable is the content?"

That Authentic Brands and others make their living acquiring these assets, but not physical infrastructure, attests to the rise of the "asset-light" business model. IP, to some extent, is a business stripped of its physical assets and operations. Licensing it out to others, as Authentic Brands, Sequential Brands and their ilk do, shifts operating costs and, with them, immediate financial risks to the operators licensing out the brand.

Along with backend technology and consumer shifts online, individual firms cropped up that "took parts of the value chain and became really good at executing that," allowing brands to stand on their own, said Matthew Katz, managing partner at SSA & Company.

But there is risk there, too. "In the near term, the upside of separating the IP from the operations gives it extensional reach either category-wise or globally that is truly significant," Katz said, adding that it can expose the brand in new ways and places.

"By separating it, the risk is … the ethos or DNA of that brand are no longer connected to its founder." By aggregating brands together into a large portfolio, there's also a risk that the original brand loses definition and differentiation. "Sameness is a challenge for all retail and all brands," Katz said.

There's also risk of alienating the brand's consumers. As just one example, some fans of Barneys, an institution of cool and high-end fashion, were dismayed last fall when the retailer's IP sold to Authentic Brands, which cut a deal with Saks Fifth Avenue to retail products under the Barneys banner. When Barneys was reportedly first in talks with Authentic Brands, New York University professor of luxury marketing and branding Thomai Serdari described Authentic as capitalizing on "the ghost of the creative brand that Barneys used to be by transforming it into a series of soul-less, licensed merchandise for mass consumption."

At the same time, there's likely little upside to buying a brand and slapping it on random products and a website without much care or thought. That's especially the case with fashion apparel — which comprises much of the IP market.

"With fashion, it's so hard now that I don't know if you would put in the effort if you weren't going to grow it," said Lauren Bitar, head of insights at RetailNext. "If the brand is a good enough cash cow that you could ride it for a while, it wouldn't have gone bankrupt."

When all is said and done, the resurrected brand still has to compete in a crowded online space. The key to success starts in the acquisition. Bitar said that she would look for sales figures. Even in brands tied to unprofitable companies, sales trends are of chief importance. Then you have to communicate to customers that the brand is still alive and out there, and show them where the brand exists digitally and physically, and if anything has changed.

"If you really need to have a new aesthetic or you're taking this equity but making a new statement about who you're going after and what you stand for, then you need to be really clear and obvious about that," Bitar said.

At the heart of all of this are some key questions about brands and retail businesses. Retail businesses fail and shut down for many reasons: management failures, excessive debt, bad luck, bad timing, and sudden, difficult-to-predict sales and customer declines. The list goes on.

None of those necessarily mean the brand itself is dead. Even a brand in decline is not dead. It could still have a substantial and active fan base, just not one that can support the infrastructure of a physical footprint. But nor is every retail brand worth salvaging after the stores close.

Here's a look at some brands that thrived and some that have languished, and some that still await judgment, in the brand afterlife beyond brick-and-mortar:

Toys R Us: From big-box giant to … ?

Toys R Us' IP was initially slated for auction as the big-box toy seller was liquidating in bankruptcy. At the time, some speculated that it might have been among the most valuable IPs ever to go up for sale. We'll never know, however, because the auction never came. Toys R Us cancelled the auction, and lenders of the retailer took ownership of the IP, which went under a new entity, Tru Kids.

That entity now runs the Toys R Us website, which isn't an e-commerce store so much as an online forum for toys. The company first partnered with Target, sending toysrus.com visitors to Target's website where customers could actually buy things. Now that role is filled by Amazon.

Tru Kids also formed a joint venture with b8ta that opened two new physical Toys R Us stores that, like the website, are more of an experiential medium and marketing platform than an actual store that makes its money off sales of inventory. The stores opened to much hype in fall 2019, but they remain the only two that the reformed Toys R Us has opened.

"The toy business is very hard," Katz said. "It's very difficult to manage at scale all year round." But a large-scale toy store is not the only option for the Toys R Us IP, now that it's been freed from its physical origins. "Can you take that brand and make it something else — smaller, pop-ups, a higher-end aggregator of toys, a label of toys and lifestyle?"

Whatever Toys R Us wants to be, it gets to do it without its past financial burdens.

"Toys R Us, they're a fresh start," Portell said. "They get to build a P&L for a toy store from scratch without having seven or eight billion in debt sitting on top of them."

Blockbuster: Mouldering in Dish's basement

Dish Network bought the Blockbuster video rental chain at a bankruptcy auction in 2011. The satellite TV provider originally planned to keep Blockbuster's physical business alive, in part to provide Dish a retail outlet to sell its wares and to cross-sell products. But by 2013 Dish closed the remaining Blockbusters that it operated, leaving only a few franchisees that eventually dwindled down to one franchise-owned store in Bend, Oregon.

Dish today still owns Blockbuster's IP, but isn't doing much with it. The company advertises on Blockbuster.com that "The Magic of Blockbuster Video lives on with DISH," but the one-page site links to Dish services that have nothing to do with the brand. Another Blockbuster-branded page maintained by Dish hasn't had any new content posted since 2013.

Here and there the brand name makes its way onto products, and the lone Blockbuster pays a fee that amounts to a rounding error for Dish. Other than that, the IP seems to be sitting there in Dish's filing cabinet.

The attention that last Blockbuster store has received is a testament to the brand's enduring value in the age of Netflix and Prime Video. Earlier this year, when the last Blockbuster offered itself up as an Airbnb, national media of all stripes wrote about it. People still care about the brand.

"Blockbuster in particular symbolizes a transitional point in media," Portell said, referring to how video rental over time gave way to streaming and other services. That makes the Blockbuster something of a "nostalgic anchor" akin to FAO Schwarz, brands that "capture a point in time where retail was fun."

Dish might not be selling the brand, but that doesn't mean it wouldn't sell. "I have a list of people who would buy it," Peress said of the Blockbuster IP. "It's not for sale. It's not for sale, and I've inquired."

Charlotte Russe: A second chance in brick-and-mortar

The Charlotte Russe brand has been on a roller-coaster ride over the past year and a half. In early 2019, the retailer filed for bankruptcy and then liquidated its entire store footprint at the end of a battle with deteriorating sales and traffic. Its IP was sold off in bankruptcy to fashion company YM Inc., which then proceeded to open more than 130 stores before the year was even out.

Will the bet pay off in a crowded — and difficult — apparel market? That's the same question hanging over many of these brands.

"They've got a lot of brand recognition and equity, which is great," Bitar said. "But to me, there's nothing that sticks out in their aesthetic that you couldn't have found somewhere else."

In all of these cases, judging success is difficult because success is in the eye of the acquirer, Portell notes. With brands like Charlotte Russe — a fashion retailer that at its height had hundreds of stores and became burdened with debt after a private equity buyout — they also are a reminder that a company's failure does not necessarily reflect the strength of the brand itself.

"Just the act of being able to shed the debt frees up the brand to then grow again and be managed however the new owner wants it to be managed," Portell said.

That said, they can't, and perhaps shouldn't, all survive.

"It's like nature's not even getting to do its thing, because instead of letting brands that are no longer pleasing consumers just go extinct, they're bringing them back," Bitar said.

FAO Schwarz: A toy icon lives on

Tom Hanks may have made FAO Schwarz's New York flagship one of the most famous toy stores in history. But fame couldn't save the store from retail oblivion. The toy seller, more than a century and a half old, went into bankruptcy and was later acquired by Toys R Us, which shuttered the famous Manhattan flagship. And then Toys R Us, of course, shut down years later.

FAO Schwarz's IP was purchased by ThreeSixty Group, which gave Sharper Image, that mall-staple purveyor of weird electronics, a successful second life after it liquidated.

Since acquisition, FAO Schwarz has enjoyed life as a product brand, sold everywhere from Barnes & Noble to Marshalls. Last year, it launched an exclusive line for Macy's stores. This year, it's working with Target for a 70-piece exclusive collection that could put it in front of a mass audience.

FAO Schwartz has also opened a new flagship in New York and is trying to keep its brand relevant through numerous partnerships with retailers and other brands.

Juicy Couture: A 'ghost' of a name

Juicy Couture was a signature brand of the 2000s, keeping the celebrities of the age — the Britney Spearses, the Paris Hiltons — draped in velour during the decade.

After it was sold to Authentic Brands, the licensing specialist closed all of its U.S. stores and moved Juicy merchandise into Kohl's, where it was sold until this year.

"They were never taken super seriously, but it just disappeared," Bitar said of the brand. "You don't have the stores, I'm not sure people really knew where they were. They just ran into the ground. They changed the aesthetic. They lowered the price, which to me says they must have lowered the quality of the materials. And so it's just not the brand anymore, which is operating with the name of a ghost essentially."

The brand's future took a hit after Kohl's opted to discontinue it and other women's brands this year in favor of more activewear lines. But, a recent collaboration with sportswear company Kappa may spark a renewed interest in the brand.

Bon-Ton: A false start on a retailer's second run?

The department store retailer Bon-Ton is a good reminder that what might seem like fate in retrospect could have played out differently. After filing for bankruptcy in 2018, the company had a "going concern" bid that would have kept it alive and operating after Chapter 11. But one of the company's lenders outbid it at auction and liquidated the assets, seeing a better payout that way.

With its stores shuttered, Bon-Ton's IP sold for $900,000 to a small, relatively unknown tech company called CSC Generation. CSC had plans to revive Bon-Ton and re-expand its footprint, with the firm's CEO, Justin Yoshimura, seeing an opportunity in a demographic that Bon-Ton reached and was left unserved by the likes of Amazon. In 2018, Yoshimura told Retail Dive that dozens of store leases were in play. To date, the company lists a reopening notice for one store, under Bon-Ton's Carson's banner, on its website, which has since closed.

"The question there in my mind is the reason for being," Katz said. "Department stores are sort of a challenge. The question for a regional department store is one of regional differentiation."

At least with the original incarnation of Bon-Ton, lack of differentiation was a fatal flaw. A department store with all the same brands as everyone else in a price-competitive market proved not to be viable. Something would have to drastically change in Bon-Ton for the model to work again.

Sports Authority and Borders: Into a competitor's dustbin

There's another category of retail IP: those whose acquirers never intended to keep them alive. After Sports Authority collapsed and liquidated in bankruptcy in 2016, competitor Dick's bought the IP. Today, if you go to sportsauthority.com, Dick's courteously redirects you to its own website.

Along with the domain and trade names, Dick's also bought itself customer lists and data, and private labels. "We clearly see it as a strategic asset for us and that's why we acquired it," then-Dick's COO Andre Hawaux said in 2016, in response to an analyst's questions, according to a Seeking Alpha Transcript. "[T]he key elements of that also was the customer names in the list and how we market to them and how we bring them over to become Dick's customers. But we see that as very strategic for us."

Barnes & Noble similarly bought the IP of its competitor Border's when the latter liquidated in bankruptcy in 2011. There, too, any would-be visitors to the Border's website get a ticket to barnesandnoble.com.