As the metaverse makes the leap into reality, marketers are eager to figure out where this new frontier fits into their strategies. However, like with other digital platforms, there is evidence that as popularity grows, so does the attention of bad actors like extremist or hate groups.

After high profile examples such as the racial slur allegedly buried in a McRib NFT, marketers are right to be wary of this new arena.

"What's tricky about it is you need to build a community where certain beliefs are, of course, geared toward one direction," said Dirk van Ginkel, Jam3's executive creative director.

However, NFTs and the metaverse are also hard to ignore as they become increasingly popular. During the Super Bowl, Miller Lite used the metaverse platform Decentraland to skirt advertising restrictions, Wrangler unveiled a new NFT to promote a music partnership and Kia used the technology to promote its big game ad.

Some of the rush to join the metaverse may be the result of brands not wanting to repeat past mistakes of sitting on the sidelines too long when fast-moving digital technologies emerged. When social media first started to become a feature of daily life, brands avoided the platform. For example, McDonald's didn't join Twitter until 2009, three years after the platform launched. Apple was even later, not joining until 2011.

Into the wild, wild internet

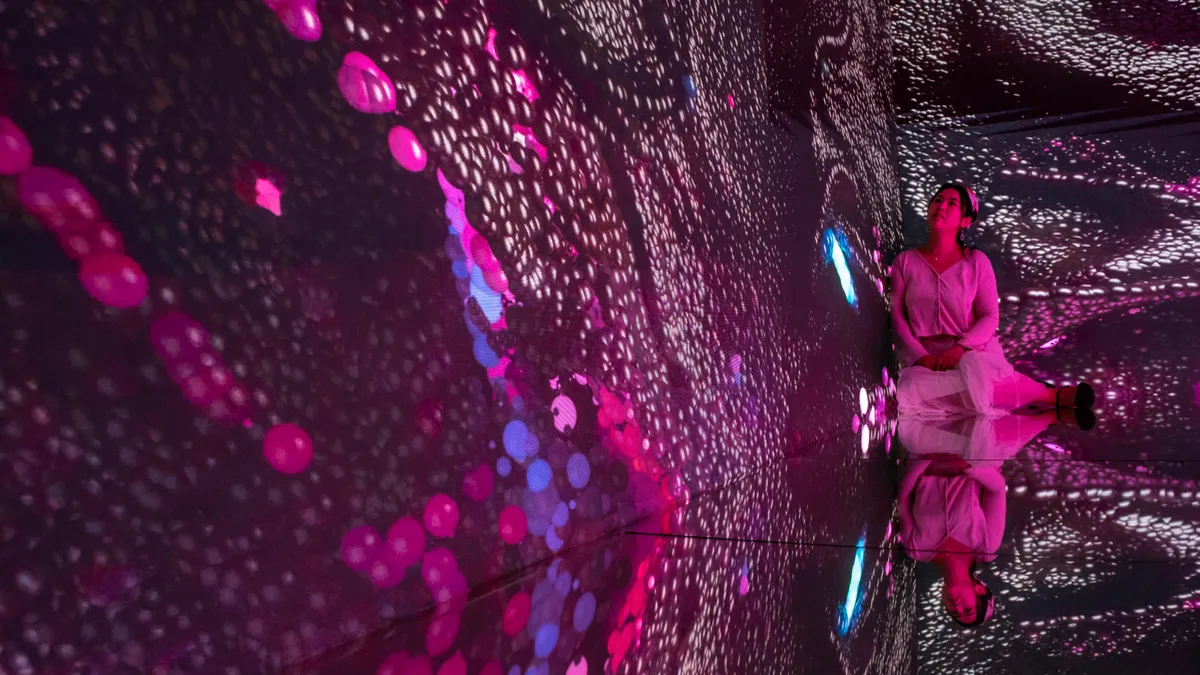

For many, the metaverse is the natural next step for the internet. Facebook changed its name to Meta, signaling a greater focus on the metaverse at a time when social media is showing signs of maturation. A connected platform where people can gather and engage in digital commerce could be the next step for social media. Brands will no longer be limited to physical spaces — or physical products — as NFTs grow in value. Instead of purchasing a bottle of Miller Lite at a physical store, beer drinkers can purchase a virtual one while attending a metaverse party.

Initially, the metaverse was hailed as a way to potentially curb hate speech online while also protecting user privacy. Think tanks such as the Oasis Consortium put forward the idea that platforms like Decentraland can help eliminate hate speech through smart contracts and community monitoring. Most metaverse spaces are user-run, meaning they have the ability to vote out bad actors.

In theory, this is great. If someone walks into a virtual bar with a slur for a username, that person can be easily voted out and ejected. However, in practice, this has proved to be less effective as one might hope. For example, the community governing Decentraland failed to gather enough votes to ban the use of "Hitler" as part of a username.

With that in mind, how do brands keep their metaverse space from being overrun by hateful players? According to experts, while hate will always exist, the metaverse may be less risky than other platforms.

"What is interesting about web3, the communities that are engaged with it are a lot more gated. So a good example is, for instance, if you want to launch an NFT for brands, there's generally a discord that comes along with it. And those communities can shoot down a discord as well. So the community is a lot more in control as to what's happening," van Ginkel said.

However, self-regulation may prove elusive. Questions remain around how things should be regulated and who should do the regulating. There are concerns that platforms like Decentraland and others over-rely on users to regulate other users, according to experts.

"The question of what … should be regulated as well as who may do this regulation is also a work in progress. In short, while some of the XR hardware and software is now here, the laws are not," Katerina Girginova, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Advanced Research in Global Communication & Center on Digital Culture and Society, said in an email to Marketing Dive.

Ultimately, it is up to brands to ensure their digital footprint remains safe, especially as questions around scalability of these methods remain.

Show me the contract

One way to enhance brand safety is through the use of "smart contracts." These are programs that are stored in the blockchain that only activate under certain conditions. If the conditions of the smart contract are violated, the program fails to run. If brands built certain rules around decorum and behavior into a mandatory smart contract before selling someone an NFT or allowing them entrance into an virtual space, they may be able to keep themselves safe.

Smart contracts may be a way of mitigating some risks for brands. However, brands should not undertake these contracts lightly, according to van Ginkel. Before setting up a smart contract, professionals who know the space well should be employed.

While many brands insist on being a part of the metaverse and producing NFTs, some don't want to be paid in cryptocurrency, van Ginkel added. This can further complicate matters if they don't want to create a digital wallet. But without a digital wallet, anyone can be ripped off in the NFT or metaverse space, as their cryptocurrency is left unprotected. Recently, concerns have arisen around the value of NFTs. Some experts believe the current NFT market is a bubble ready to burst. While the technology is here to stay, NFTs, which are the backbone of the metaverse, come with a level of speculation that not everyone is comfortable with.

While wallets and smart contracts have the potential to keep brands and consumers safe in the metaverse, educating people on how they work is likely to be a challenge since many don't understand what it entails. Currently, just 38% of Americans are familiar with the metaverse, and 42% of those familiar with the platform can correctly describe what it is, per Ipsos research.

"I think as a brand, it's always important that you explain to your audience that it's always good to get a physical wallet, for instance," van Ginkel said.

We're not ready for this

Despite the hype, the metaverse is a technology still very much in its infancy, and its ability to gain wider adoption could be hurt as a broader reckoning around digital privacy takes place. Concerns have arisen over the sheer amount of data that the metaverse will create on its users, such as biometrics.

With the technology being so new, some experts are asking if brands are moving too fast given how consumer adoption remains low.

"There hasn't been any platform in the history of the internet that has started with brands being present there first. It always starts with people first, and they need to have the interest," van Ginkel said.

Part of the problem for consumers is that the user experience in the virtual space is currently subpar, per van Ginkel. It takes too long to set up an avatar, and for many brands, the novelty of the metaverse alone may not be enough to compel users to join. However, for brands with an established connection to youth culture, consumers may be willing to overlook the metaverse's issues. For example, Nike's fan base may be willing to use the tech to engage with their favorite brand, but a newer company attempting to use the metaverse to establish itself may see lackluster response.

Another drawback for marketers is that currently, a united metaverse doesn't exist, according to Jack Cameron, co-founder of metaverse marketing company Luna Market. There are several metaverse platforms, but interconnectivity has yet to be achieved. Brands that focus too much on onboarding may miss the whole point of virtual connection and interaction. At its core, the metaverse is a game, according to Cameron. So while it's a way for people to pass time online and connect with friends, the metaverse shouldn't be treated like other social media platforms. Instead, brands should think in terms of video games and design their strategy to fit what makes gaming appealing.

"I think people who focus on just onboarding lose sight of what makes a game good. It's how you play and how it feels to play it," Cameron said.