In a case of cinematically bad timing, three of the largest retail projects to hit the New York City metro area opened less than a year before a historic pandemic shut everything down.

Each development was designed to appeal to well-heeled tourists, and each loomed large in both scale and scope. The 750,000-square foot Shops & Restaurants at Hudson Yards opened on Manhattan's far West Side in March 2019, and brought with it the promise of a revitalized neighborhood bustling with luxury. Then the 3.3 million-square-foot American Dream Mall which opened in October 2019 just across the Hudson River in East Rutherford, New Jersey, was finally completed, and offered an over-the-top combination of retail and indoor entertainment options. Finally, Nordstrom opened its first New York City flagship store, a 320,000-square-foot emporium on Manhattan's 57th Street in October 2019, directly across from its 47,000-square foot Men's Store, which opened in April 2018.

New York City has been the site of several big retail splashes before, such as The Shops at Columbus Circle, a 338,500-square-foot retail space owned by The Related Company, which also owns Hudson Yards. But the timing of these new developments seemed to confirm the city's status as a demesne for the 1%, home to more millionaires than any other place in the world.

That was before. When COVID-19 hit the U.S., New York City suffered through the worst of the pandemic early on. Retail was hit particularly hard, and tourism ended abruptly. The wealthier residents fled, and published goodbye letters to the city they declared was now over. Suddenly, luxury retail seemed like a bad fit for the times. In August 2020, even Related's billionaire developer Stephen Ross declared that New York City was overpriced.

Pre-COVID optimism

It's not just the New York Metro area, of course. Coresight Research reported that retailers across the country are struggling, and are expected to close up to a record 25,000 stores this year.

But the sheer opulence of these new projects has magnified their challenges. Hudson Yards, for example, is one of the most costly mixed-use developments in the country, and has had a notably tumultuous year. The retail space, which did not respond to request for comment, opened with anchor tenant Neiman Marcus as its crown jewel, alongside fine dining options, office space, and upscale residential apartments. Yet within a year, COVID forced retail closures, and office spaces emptied as workers were forced to telecommute.

By April 2020, 75% of Hudson Yards' retailers reportedly had stopped paying rent. Then in July 2020, Neiman Marcus ended its lease amidst bankruptcy negotiations, and Thomas Keller's TAK restaurant also shuttered. Now, Hudson Yards is open without two of its biggest attractions, no publically released plans to fill the vacancies, and no guarantee that the workers who made up much of its customer base will be back at their desks any time soon.

Less than ten miles away, the American Dream mall, which declined to comment for this story, is another sprawling testament to pre-COVID optimism. The huge retailtainment project was forced to temporarily shut down due to the pandemic less than a week before its retail component was scheduled to open. But that was just one more bump in an already rough road.

As reported by Bloomberg, the mall endured more than 16 years of financial and legal troubles, and development group Triple Five, which also owns Mall of America, is now eyeing $5 billion of debt. Five of its original tenants — CMX Cinemas, GNC, Lord & Taylor, Forever 21, and Barneys New York — pulled out of their leases before declaring bankruptcy, and at least two other stores, Victoria’s Secret and The Children’s Place, are faltering.

Possibly as a reaction to the retail problems, Don Ghermezian, CEO of Triple Five and co-CEO of American Dream, told CNBC in April that the mall would shift from 55% entertainment-related tenants and 45% retail to a more experience-oriented 70% entertainment and 30% retail. When the mall reopens on October 1, only a handful of retail tenants will be ready to serve customers, and Bergen County's blue laws still prevent stores from being open on Sundays.

On a smaller scale, Nordstrom is also experiencing some upheaval. In an email to Retail Dive, a Nordstrom spokesperson explained that by Q2, Nordstrom had "significantly reduced inventory to mitigate markdowns." The spokesperson also addressed the question of Nordstrom's rent reduction negotiations, saying, "We paid rent to our landlords through May, and as part of our continued efforts to navigate this situation, we are modifying our rent payments until January 2021, at which point we’ll fully reconcile our payments."

In its Q2 earnings call, CEO Erik Nordstrom said the company had permanently closed 16 full-line stores, and explained that Nordstrom's "big urban stores, in general, have been harder hit by COVID than other areas." He noted that New York City was particularly emblematic of that issue, since its population density had led to a "bigger drop-off in traffic." On that same call, Anne Bramman, Nordstrom’s CFO reported a Q2 sales decrease of 53%.

Not just COVID

Though stores and developers have been quick to blame COVID-19 for their 2020 challenges, retail's problems were only enhanced — not created — by the pandemic.

"Pre-COVID, we had a downturn in tourism, and in particular Asian tourism, for some of our urban core retail," said Todd Caruso, senior managing director, Americas, at commercial real estate firm CBRE. "There was also a rethinking of real estate in high end urban rental markets a couple of years back." Caruso said that as omnichannel options grew, many retailers began to reevaluate the value of operating expensive brick and mortar stores.

"Because of the e-commerce pressure that's evolved over the last couple of years, if you're a retailer, you're scrutinizing every decision you make," he said. "So when rent got really exorbitant, [retailers] had to look at the return on invested capital. It [costs] thousands of dollars per square foot [to rent] in New York City. And just when we saw rent starting to decline, COVID hit. Now tourism and travel are down, and there are department store challenges."

A drop in tourism wasn't the only problem. "With COVID, there's a shock to the system on the foot traffic side, both from a tourist perspective and a local people perspective," said Andrea Szasz, a principal in the consumer practice at Kearney, a global strategy and management consulting firm. "But let's say this is a temporary situation. There are still other trends. People are shopping more and more online, and the amount of shopping that happens across physical and digital has boomed."

Digital solutions

One solution that addresses both COVID-cautious and future-facing retail is to enhance and build out digital solutions so that consumers can stay connected even when they can't physically engage. "The idea is that the consumer wants a frictionless experience, and community, and a relationship with the retailer beyond a physical box," said Deborah Weinswig, founder and CEO of Coresight Research, a global advisory and research firm specializing in retail and technology. "But the fact is we haven't seen centers investing dollars in new technologies to be able to serve their customers better. They have to do this now. It's not even a when, it's a now. That's been a challenge we’ve seen for many companies."

Some stores have already begun addressing this. Nordstrom said consumers were engaging more with digital sales, which helped make up for declines in foot traffic during the first half of 2020. "In our digital businesses, traffic grew by double-digits year-over-year [in Q2] and sequentially improved from Q1, indicating signs of increasing customer demand," the Nordstrom spokesperson stated. "As we experienced last quarter, we had more than 50% growth in new Nordstrom customers through our digital platforms."

"The fact is we haven't seen centers investing dollars in new technologies to be able to serve their customers better. They have to do this now. It's not even a when, it's a now. That's been a challenge we’ve seen for many companies."

Deborah Weinswig

Founder & CEO, Coresight Research

Szasz said that larger developments, such as malls, will need to take notes from digitally-savvy retailers if they want to maintain engagement. "With COVID, the key for the perfect experience is one that's contactless from a functional perspective, for things like payment and product, so that you feel safe," said Szasz. "The other element is experiential. I have to have a reason to go to the mall, because people have been isolated for so long, and they crave contact with people, but within an environment that will make them feel safe."

Mall developers need to find ways to digitally connect with customers. "Shopping malls could create an online experience, and mirror foot traffic with eyeball traffic, and let customers shop services and browse the mall online and make it a real omnichannel experience," said Szasz. "Is there a way to create a more cohesive online experience to mirror the digital space?"

Rethinking the mall

Evolving digitally isn't just about connecting with customers during the pandemic. It's also about creating a more economically sustainable business later on. "I'm really impressed with the owners who are sophisticated," said Caruso. "Some portfolio owners of large format retail assets in enclosed malls have invested in the science side to learn who their true customer is, because they want their property to be the town center."

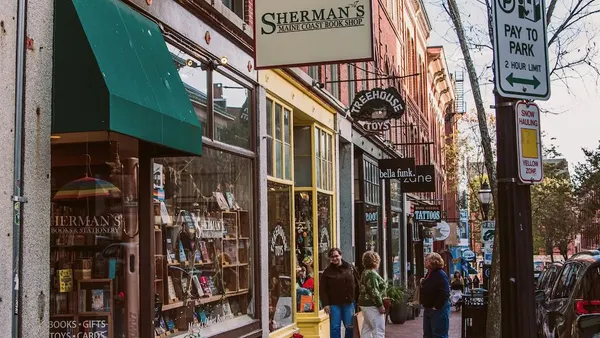

Smaller, more niche retail may play a bigger part moving forward than larger, international brands. "We're seeing a significant decline in tourism," said Weinswig. "Landlords not only have to make their centers a shoppable experience, but then also localize it, and have localized assortments. Is there a way to connect that to the consumer?"

Weinswig said the technology already exists to make this happen, and she sees it as an opportunity rather than an expense. "We're speaking to large landlords, and the idea is, let's bring in local artisans. It could be a workshop, and you could change the trajectory of hundreds of vacancies. As Neiman Marcus is exiting, you instead invite designers in, and maybe there's a competition around it. You invite local designers and retailers, and give each of them a set amount of space. Maybe it’s truly an atelier. It's an opportunity to rethink the mall."

"Just because you have an enclosed mall, or just because you build a lifestyle center, doesn't mean it will work."

Todd Caruso

Senior Managing Director, Americas, CBRE

Shifting toward a community model also means incorporating a multifaceted range of businesses, and exploring tenants that offer services beyond retail, entertainment, and food and beverage.

"Owners are saying, 'If I am committed to being the heartbeat of the community, I'm committed to being a town center, and not just three or four department stores and some retail and a few [food and beverage],'" said Caruso. "Investors have fallen prey, in some instances, to letting the format lead the merchandising, rather than letting the customer and the demand in the market lead the market. But just because you have an enclosed mall, or just because you build a lifestyle center, doesn't mean it will work. It goes back to the real estate, and understanding the customer and where the demand is. I applaud the fact that some owners incorporate financial services and medical retail and residential and coworking and offices."

Caruso said that ideas about the ideal tenant mix were already shifting pre-COVID. There was growth in food and beverage, he said. "Seven to ten years ago, it was only 15% of space, and then it started to grow. Will they replace department stores? I think owners will take a step back and see that apparel is under stress because of e-commerce. Owners are thinking they have to have the right amount of food, apparel, entertainment, and wellness. I don't know if entertainment will change post-COVID, but owners are rethinking the mix of those users."

Caruso said it's up to retailers to find new ways to actively engage consumers within their existing properties. "When they do the studies and look for where there's a need, they recognize there's a demand for this," he said. "Of course, we'll always see properties owned by passive owners, where the assets have been languishing, and they're bleeding it. And those places that were dying a slow death are now dying a rapid death."

Yet he remains optimistic, too. "The industry has been hit pretty hard in the press, but I've seen many, many cycles," he said. "The industry is just so resilient, and they’re transforming in front of our eyes."

Community, not corporate

The prospect of obsolescence — whether it's COVID-related or simply COVID-adjacent — may be what finally drives sluggish large scale retailers to embrace this transformation. "Even when you're seeing your sales or margins stagnant or decline, change is really hard," said Weinswig. "But now it's tough conversations and tough love. [Some businesses] don't move that fast. And a lot of the pushback over time has been because it was okay to not move quickly." Weinswig said that heel-dragging is no longer possible, however. "Now, for many reasons, not only are we seeing inspiration in terms of using technology to make a difference, but also collaboration. E-commerce penetration drove a wedge in, in terms of trust between tenants and landlords. But everyone will adjust."

That adjustment will have to come quickly, because of the challenges highlighted by the pandemic. But large scale retail projects that are able to shift to more community-and digitally-enhanced models will be able to capitalize on those changes both during and after the pandemic. "Humans are social animals," said Szasz. "Whether the work-from-home situation lasts or not, after COVID, we'll be looking for places to gather, and we'll be looking for experiences."

It's even conceivable that community will matter more after the pandemic than it did before. "It's the role of a community manager to bring people together," said Weinswig. "If there's a mall manager, they need to reach out, and everyone needs to be part of the community: the store manager, the customer. And it's not just about New York. We need all the landlords to think about it. They have to digitize Hudson Yards, so that even if I'm living in Malaysia, maybe I go or never go, but I can be part of that community." Weinswig said that in turn, the community can help manage the direction of its space. "Utilize that community and pull in how they want to engage," she said. "The community doesn't own the center, but it controls the ethos of it, and provides information to the landlord."

That kind of shared experience and shared responsibility may change what malls and flagship stores mean to the communities they inhabit. It could also, potentially, provide a more sustainable path forward, and one that's better able to weather economic downturns.

"I want to know that my community is giving back, like giving free space to struggling designers, or giving away two percent of its profits. It has to feel like my Hudson Yards, or my American Dream mall. There's a mall in Thailand called Ecotopia that's like this. We may not be able to go there in person now, but I want to go there in my mind. And that's key. There are other ways to intersect, but many of the landlords are thinking at a corporate level as opposed to on a community level," Weinswig said.